The Schism of 1054 marks the official breach that separated Roman Catholic Christianity from Orthodox Christianity. It occurred when delegates of Pope Leo IX (1049–54) excommunicated Michael Keroularios, patriarch of Constantinople (1043–58), and his associates. The patriarch, in turn, excommunicated the papal delegates.

These mutual condemnations tore Christendom into its Catholic and Orthodox branches. The ecclesiastical division became permanent in the following decades, particularly because of the effect of the Crusades and their impact on Orthodox-Catholic relations.

The quarrel that led to these events surfaced by the ninth century when Byzantium was emerging from the long controversy called iconoclasm and was engaging in a new period of missionary activity in eastern Europe (and elsewhere).

|

At the same time Western Christians were expanding, moving Latin Christianity farther east into the Slavic kingdoms of eastern Europe. Missionaries bearing their respective forms of Christianity (Greek and Latin) met in the kingdoms of Moravia and Bulgaria. During this interaction certain differences in practice became evident.

The two forms of Christianity used different languages in their liturgy (Latin in the West and Greek in the East, though the Eastern Christians also supported the use of native languages for worship and Scripture and developed the Cyrillic alphabet for this purpose among the Slavs); they had different rules on fasting; they differed in their eucharistic practice with leavened bread used by Eastern Christians and unleavened by Western. Another distinction was the official acceptance of married priests among the Eastern Christians, though bishops could not be married.

Furthermore the two forms of Christianity were at odds over their understanding of papal leadership. From the Eastern perspective the pope received the primacy of honor among the bishops, since his was the church diocese of St. Peter, but he was simply one of the five great regional leaders called patriarchs who were all needed to hold an ecumenical council (churchwide) to decide doctrine.

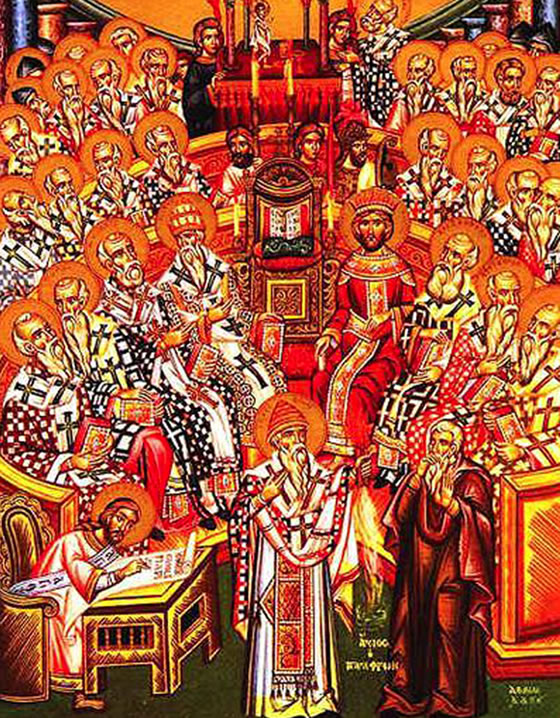

From the Western perspective, however, the bishop of Rome was also the heir of St. Peter, and the supreme voice in Christendom. Finally another important distinction was a small difference in the profession of the Nicene Creed by Western Christians. This creed was established by the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325 and augmented by the Second Ecumenical Council in 787.

This creed was used as a simple definition of faith, professing belief in the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, “which proceeds from the Father.” In the West the term filioque (and the son) was added to the latter phrase to exclude heretics from professing it.

This addition received official sanction by the papacy in the early 11th century. Eastern Christians viewed this as a mistake both theologically (arguing that it confuses the proper understanding of the Trinity) and ecclesiastically (arguing that only an ecumenical council could change the creed).

In addition to these matters the breach in 1054 is connected to other historical developments in the 11th century. This period witnessed the development of the papacy as an institutional entity freed from lay control and able to assert its authority in Italy and abroad.

One 11th-century pope, for example, asserted that he had the power to depose and reinstate bishops and emperors and that he was above any earthly judge. At the same time, the Byzantine Empire had reached its political apogee and its church was led by one of its strongest willed patriarchs, Michael Keroularios. The revived papacy and the powerful patriarchate crashed together in the summer of 1054.

A final factor influencing the breach was the arrival of the Normans in Italy in the 11th century. The Normans (from Normandy in France) passed through Italy en route to the Holy Land for pilgrimage and, because of their renowned military skills, were hired as mercenaries by rulers in southern Italy.

The Normans soon took advantage of this situation and seized southern Italy. This brought them into conflict with both the papacy, whose lands were threatened, and Byzantium, which also had holdings in southern Italy.

The Byzantine emperor wanted to maintain good relations with the papacy to ensure an alliance against the Normans, but the patriarch of Constantinople was little concerned with this political perspective.

|

| Schism map |

Furthermore the Normans closed churches in their territory that used the Greek ritual, while the patriarch of Constantinople did likewise for those of non-Greek ritual in his territory.

When the legates of Pope Leo IX arrived in Constantinople in 1054, they demanded that the Eastern Church accept the Western view on the papacy and certain other practices. When this failed, they excommunicated (cut off from communion) the patriarch and his associates.

Keroularios, in turn, anathematized (condemned) the authors of the excommunication. There had been numerous schisms before between Constantinople and Rome that had been mended afterward, but the Schism of 1054 became permanent.

|

Historical circumstances in the following decades transformed the theological condemnations into a seemingly permanent cultural divide between Catholic and Orthodox. The first change occurred shortly after the schism when the papacy shifted its policy toward the Normans from one of hostility to one of support.

The Normans now acted with the support of the papacy as they finished off the Byzantine possessions in southern Italy and seized Sicily. With these positions the Normans began to eye the Byzantine Empire as their next goal for conquest.

This threat to the Orthodox empire was augmented by new challenges from the north (a pagan, Turkic tribe called the Pechenegs) and a massive challenge from the east in the Muslim Seljuk dynasty, who took control of Anatolia as well as much of the Muslim world.

The emperor Alexios I Komennos (1081–1118) appealed to Pope Urban II for military assistance. Pope Urban called for a massive undertaking, not simply to assist Byzantium, but to recover the Holy Land from the Muslims.

Thus the First Crusade was born. Tens of thousands of Western soldiers as well as clerics passed through Byzantium. This movement of Westerners, including the Normans who were already actively hostile to Byzantium, increased tension between Orthodox and Catholic.

The emperors were concerned that crusaders might not simply move through the empire, but conquer parts of it. This fear greatly increased during the Second and Third Crusades in the 12th century and was fully realized when the Fourth Crusade was diverted to Constantinople.

In 1204 Western crusaders sacked this city and conquered the Byzantine Empire. A Catholic patriarch was installed at Constantinople (until 1261). These events, most particularly the last, transformed the Schism of 1054 from a theological dispute to a near permanent cultural divide between East and West, Orthodox and Catholic.