|

| Samarkand |

Samarkand and the neighboring city Bukhara were oases along the valley of the Zeravshan River. Agriculture thrived in the region from the eighth century b.c.e. Formerly known as ancient Afrasiab, the city was founded during the seventh century b.c.e.

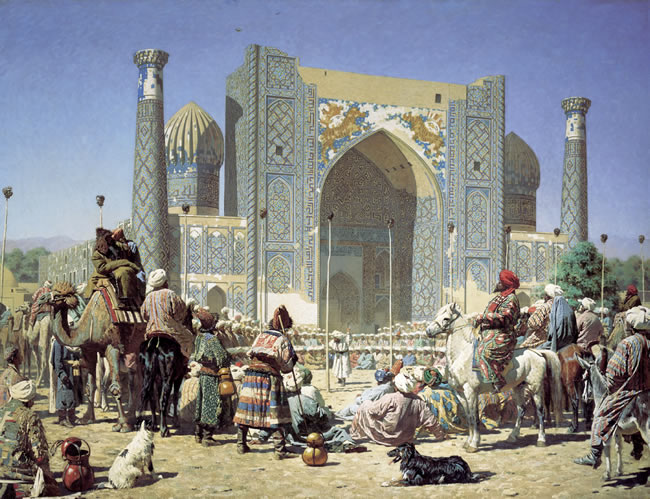

Samarkand was surrounded by walls and was famous for its opulent architecture. Its strategic location along the Silk Road, which spanned China and Europe, contributed to its economic success and cultural vibrancy.

One route along the Silk Road known as the Golden Road was of particular importance to the rise of Samarkand and Bukhara as key trading hubs. The Golden Road passed through the principal cities of Mesopotamia and was extremely busy, frequented by many traders.

|

Samarkand became a cosmopolitan center of science and art, as new scientific and artistic ideas were transmitted rapidly along the Silk Road. For most of its history, the Achaemenid Persians made Samarkand the capital of their empire. Alexander the Great conquered Samarkand (or Marcanda, as it was then known) in 329 b.c.e. after overthrowing the Persians.

By the eighth century trade and culture flourished in the city. An Arab chieftain, Qutaiba ibn Muslim, the governor of Khurasan, invaded Samarkand in 712 c.e. Qutayba’s alliance with local Khwarazmians (who supplied him with knowledge of the surroundings as well as use of new technology in the form of mangonels, a heavy war engine for hurling large stones and other missiles) enabled his forces successfully to invade the city. Qutayba reneged on his promise to the Khawarazmians and expelled non-Muslims from the city.

From the eighth century, Samarkand became the center of the Umayyad dynasty. It was during this period that Samarkand was established as the center of Islamic civilization. In the ninth and 10th centuries Samarkand was ruled by the Abbasid dynasty and continued to be a major center of Islamic civilization.

The city retained its prominence as the capital of the Samanid dynasty and later, of the Seljuks (Turks) Empire. Sometime during the 13th century, the Venetian traveler Marco Polo reached Samarkand, and he described it as “very large and splendid.”

|

| Timurlane era |

In 1220 the Mongols led by the powerful ruler Genghis Khan attacked the city. The destructive siege left Samarkand devastated. The city was left in ruins, but it did not experience total destruction for the Arab traveler Ibn Batuta recorded his observations of Samarkand as “one of the largest and most perfectly beautiful cities of the world,” supporting the view that certain vestiges of the city were still standing.

Among all its conquerors the fourth one, Timurlane (Tamerlane), a nobleman originally from a littleknown Turkic tribe, made the biggest impact on Samarkand. The despotic ruler made Samarkand the capital of his empire and rebuilt it in 1370 south of the old site.

By sparing all master craftsmen, including architects, from death upon his invasions, he was able to employ them in his service. Samarkand developed into a well planned urban civilization. Timurlane’s patronage led to the construction of many religious schools known as madrassas, grand mosques, mausoleums, and palaces.

|

Timurlane also made popular the use of turquoise ceramic. The enormous Bibi Khanum mosque added to the splendor of the city. Upon returning from his victory in India, Timurlane built the Bibi Khanum mosque in honor of his consort, Saray Mulk Khanum.

The Timurid phase occupies a distinct place in Islamic architecture, because of the wide use of ceramics. Building materials were not found in Samarkand and builders made mud bricks (out of clay, chopped straw, and camel urine) that were faced in glazed tiles in blue (Timurlane’s favorite color). These were then fashioned into minarets, portals, and domes.

The new city of Samarkand built by Timurlane was vastly different from the old city and was based on the Tatar concept. Under Timurlane, the city of Samarkand was home to Arabs, Persians, Turks, and North Africans of diverse sects as well as Christians, Greeks, and Armenians.

Timurlane’s grandson Ulugh Beg succeeded him, making Samarkand a major scientific hub by building an observatory. In his zeal to make Samarkand a center of learning Ulugh Beg also built two madrassas in the neo-Persian style, the Shir Dar and the Tilla Kari.