|

| kingdom of Poland map |

The history of the kingdom of Poland is traditionally dated from 966, when the 31-year-old Mieszko I, of the Piast dynasty of the Polans tribe, was baptized into Christianity. The country derived its name from his tribe. He was married to Dobrawa, the daughter of Bolesław (Boleslas) I of Bohemia, a strategic nuptial alliance that brought him a relationship with the Holy Roman Empire in his feuding with the Wieletes and Volinians.

Wichman, count of Saxony, who was also a noble of the empire, backed them. Thus Mieszko’s marriage gave him a strong counterweight to his enemies. Most likely his conversion to Christianity was a prerequisite to the marriage.

In a move designed to cement his diplomatic position, Mieszko I also swore allegiance to Emperor Otto I the Great. This was essential to his plans for expansion of Piast lands. In 955, 10 years before Mieszko I’s conversion, Otto had cemented his primacy throughout central and eastern Europe.

|

In 955 he decisively defeated the invading Magyar tribe at the Battle of the Lechfeld, near Aubsburg in Bohemia. As David Eggenberger writes in An Encylopedia of Battles, “the Germans crushed the Magyars with heavy losses in a tenhour battle. The decimated barbarians fell back across modern Austria.”

They settled in what became Hungary, which still recalls its heritage on its postage stamps with the inscription Magyar Posta. By his death in 992 Mieszko I had considerably expanded his realm, including not only what was then known as Little and Greater Poland, but also Pomerania and Silesia.

Throughout his reign, he assured himself of at least the quiet complicity of the Holy Roman Empire, by swearing allegiance, after Otto I, to the emperors Otto II and III. As a loyal vassal he supplied troops to Otto III in his campaign against the Polabians, Slavic tribesmen who lived along the Elbe River.

|

| Polish cavalry |

Mieszko I was succeeded by his son Bolesław the Brave, his son by Dobrawa. (He also had children by his second consort, Oda, three sons: Mieszko, Lambert, and Swietopełk.) Bolesław continued his father’s wars for Piast aggrandizement. In 999 he seized Moravia and next conquered Slovakia. When in 1002 Otto III died prematurely at the age of 22, Boleslas took the ultimate gamble and attacked the Holy Roman Empire while it was in a succession crisis for the throne. Emperor Henry II, duke of Bavaria, was ultimately crowned emperor in the place of his deceased cousin in June 1002.

Bolesław’s aggression against the empire set off a series of struggles between him and Henry II, which would eventually lead to a compromise peace in 1018. Bolesław was compelled to return Bohemia to the empire, although the empire was recognizing Bolesław’s strength, and Henry did not contest Bolesław’s keeping Lusatia and Misnia. He wisely pledged allegiance to the emperor. But in 1025 a year after Henry II’s death, Bolesław crowned himself the first king of Poland and freed himself of any feudal obligation to serve the emperor.

His son Mieszko II, who had already gained experience by ruling the city of Kraków for his father, succeeded Bolesław. Mieszko II, seven years after he became king of Poland, resumed his father’s assault on the empire. The duchy of Kiev, under Yaroslav the Wise, not forgetting Bolesław’s intervention, made common cause with the Emperor Conrad II, so that Poland was invaded from both the east and west.

|

First forced to flee to Bohemia, Mieszko II eventually reconquered his kingdom and, after swearing allegiance to Conrad, was able to resume the kingship. He was assassinated in 1034, most likely the victim of a plot by the Polish nobility.

Casimir (Kazimierz) I succeeded his father as king and, unlike his father and grandson, followed a policy of peace and reconciliation. A peasant revolt followed the murder of his father and, taking advantage of the turmoil, the Czechs invaded in the south.

What was then known as Greater Poland was so devastated that the royal capital became Kraków in Little Poland, which apparently was considered loyal to Casimir and to his father before him. Prior to the choice of Kraków, the kingdom had had no real center of administration.

The new Emperor Henry III, however, feared the growing anarchy in Poland and eastern Europe, concerned that the unrest could spread to Imperial lands. Consequently he negotiated a peace among the belligerents, which confirmed Casimir as king of Poland in the first year of his reign, 1046. Confirmed by the emperor, Casimir served as king of Poland until 1058.

Upon the death of Casimir, Poland entered a period of instability, a condition that would appear throughout much of the country’s history. Casimir’s son Bolesław II ruled as duke from 1058 and was only crowned king in 1076. Three years later he was forced into exile. His brother Ladislas (Władysław) I Herman succeeded him; however he soon resigned the kingship.

Bolesław III, the son of Ladislas, was able to restore the royal authority in Poland, and effective government was restored. Bolesław III reigned from 1102 to 1138 and even succeeded in defeating the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V twice in battle. However out of diplomatic expediency, he later swore allegiance to the Emperor Lothair II, Henry’s son.

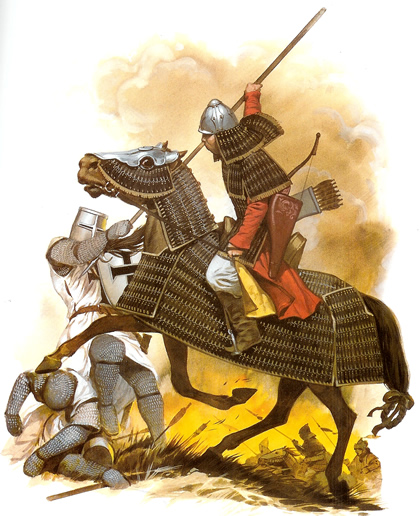

Mongol Invasions

|

| Mongol Invasions |

The death of Bolesław in 1138 signaled the beginning of almost 200 years of domestic strife, as rival members of the Piast dynasty struggled for supremacy. Poland, which under Miesko I had been a dominant power in eastern Europe, was reduced to a small player in international affairs.

The explosion of the Mongols into Europe in 1240 destroyed the entire strategic balance in eastern and central Europe. In 1223 during the reign of Genghis Khan, the Mongol warlord Subotai had smashed the Kievan army in the Battle of the Kalka River.

In December 1237 the Mongols took Riazan and began a systematic campaign of crushing the Russian city-states. On December 6, 1240, according to Eggenberger, the Mongols stormed into Kiev, “plundering and killing at will. Kiev was burned to the ground.”

This time, rather than making a large raid as the invasion of 1223 really had been, the Mongols had come to stay. While Subotai and Batu Khan continued west, directly threatening weakened Poland, the khanate of the Golden Horde was established on the “lower Volga,” according to Eggenberger. “For most of two centuries, most of Russia south of Novgorod lay under Asiatic suzerainty.”

After the conquest of Russia Subotai and Batu headed directly into Poland and Hungary, having divided their army into three parts. Fighting for Ogotai Khan, who had succeeded Genghis Khan in 1227 as the great khan in 1241, the Mongols virtually crushed the military power of eastern Europe, leaving Piast Poland in serious jeopardy. During the Mongol (or Tatar) assault on Poland, they headed toward the city of Kraków. There one of the truly heroic episodes of military history took place.

On the Rynek Glowny, or Main Market Square, stood St. Mary’s Church. According to Polish legend, an elderly watchman saw the Mongols approaching and sounded the trumpet call of the Hejnal to alert the town. Since the trumpet was played regularly, nobody was alarmed at first. But when he played it over and over, the townspeople became alarmed. Suddenly, the trumpeter stopped playing.

They saw the Mongols coming closer, and volleys of arrows from Polish archers drove them back. After the battle, somebody climbed up to the tower and found the old watchman dead, a Mongol arrow through his throat. In honor of his saving the city, the Hejnal is played every hour.

The Order of Teutonic Knights

|

| Teutonic Knights |

The power vacuum created by the implosion of Piast Poland also faced another threat from the west, a condition that would mark Polish history. In 1190 the Teutonic Knights, an order of crusaders, was established. Pope Celestine III confirmed the order as a religious order of knights in 1196, as did Innocent III in 1199. Yet unlike the Knights Templars and the Knights Hospitallers, the Teutonic Knights would not make a name for themselves in the Holy Land.

Instead, as H. W. Koch writes in Medieval Warfare, the Teutonic Knights “remained a purely German movement ... particularly in the context of its long-term development of the German east.” The Teutonic Knights’ drive to the east became a permanent threat to the stability of Poland and the Lithuanian princes to the east.

Conrad (Konrad) of Masovia, son of Casimir II of Poland, asked the Teutonic Knights for their aid against the fierce and pagan Prussian tribes. In order to bring the Teutonic Knights to accept his offer, he ceded to them Polish territory around Kulm on the Vistula River. As crusaders, the order was happy enough to take on the Prussians at the request of the Polish ruler.

Pope Honorius III in 1226 issued the Bull of Rimini to give papal backing to the coming war against the Prussians, in fact raising it to the status of a crusade. But, along with the crusade against the Prussians, the Bull of Rimini gave the order rights to make its first expansion into Polish territory.

The land around Lobau and Kulm was speedily converted by 1230, and Conrad of Masovia, apparently seeing no threat to Polish sovereignty, obligingly handed it over to the Teutonic Knights. By the time that the grand master of the order, Hermann von Salza, died in 1239, Koch notes, “the Order controlled more than a hundred miles of the Baltic coast.”

A Prussian uprising took the order by surprise in 1261, and it was not until 1271 that the order gained the upper hand. But when it did, the Teutonic Knights again focused on their expansion eastward. Danzig became part of the realm of the knights, and in 1309 Grand Master Siegfried von Feuchtwangen made the expansion a definite war aim of the Teutonic Order, while Ladislas Łokietek (Elbow-high) was the king of Poland.

Ironically it was under Wladyslaw that Poland began to regain its unity and strength. The first open clash between the Poles and the order came in 1311, when the order supported John of Luxembourg, the king of Bohemia, in his bid for the crown against Ladislas.

John and the order were defeated, but the war marked the onset of almost a constant state of tension and intermittent fighting between the Teutonic Order, the Ordenstaat, and the Polish monarchy. Casimir III of Poland began to rebuild his country’s military position in the 1340s for what began to look like an ultimate reckoning with the Teutonic Knights.

In 1385 Jogaila (Jagiello), the grand duke of Lithuania, married Queen Jadwiga of Poland, converting to Christianity. He ruled Poland as Ladislas (Władysław) II. In 1226 Lithuania had become united when the Lithuanians under their leader, Mindaugas, had defeated the Livonian Knights of the Sword (allies of the Teutonic Knights), at Siaulai.

This marriage, the result of the Union of Krewo, established the Jagiello dynasty and became the foundation of Polish resistance to the territorial expansion of the order. Meanwhile the rule of the order had grown more oppressive, through both taxation and demands on military service, to persecute the war against the Poles and their Lithuanian allies. Both Prussians and Pomeranians looked to their former enemies, the now united Poles and Lithuanians, for relief against the Ordenstaat.

In 1407 his brother Ulrich, who showed contempt for the abilities of the Poles and Lithuanians to confront the Ordenstaat, succeeded Grand Master Konrad von Jungingen. In 1410 the order’s grand master Ulrich von Jungingen decided to force the issue before Wladislaus II and a Polish-Lithuanian force could reach the order’s headquarters at Marienberg in Prussia.

On July 15 the Teutonic Knights met the combined Polish and Lithuanian forces at Tannenberg, or Grunwald. Wladislaus’s cousin, the grand duke Vytautas of Lithuania, commanded the actual Polish field army.

In the fierce combat that followed, as Koch writes in Medieval Warfare, “the Poles concentrated their attack at one point of the German front, broke through and then with their numerical superiority of 3:1 engulfed the army of the Teutonic Order and defeated it.”

Although Tannenberg was the decisive battle of the war, the knights did not surrender or cede their territory, and the struggle was continued by Ulrich’s successor Heinrich von Plauen, the 24th grand master of the Teutonic Order. For over 50 years hostilities continued between Poland and the order.

At the same time among the Prussians and Pomeranians, resentment continued against the exactions of the Ordenstaat. Finally the situation became untenable for the Teutonic Knights. In 1454 the Prussians directly approached King Casimir IV of Poland for aid in throwing off the order’s rule.

In what became known as the Thirteen Years’ War, the Prussian Confederation fought with Casimir IV against the Teutonic Order. Lithuania, the ally of Tannenberg, was also at war with Poland but did not side with the order.

In one of the first battles of the war at Chojnice in April 1454, Casimir IV was defeated in his attempt to take the city by the order and mercenaries under Bernard Szumborski in its pay. Eventually, however, the prolonged struggle outstripped the ability of the order to continue the fight.

Pope Paul II, with both warring parties being Roman Catholics, stepped in to help negotiate a settlement. By the terms of the Treaty of Thorun in 1466, the order ceded control of Prussia. Prussia became a vassal state of the Polish Crown under King Casimir IV, who now ruled a unified Poland, which would emerge as the strongest state in eastern Europe.