Alexander Nevsky, a Russian prince named after his victory over the Swedes on the Neva in 1240, was the son of Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise (Vsevolodovich), who was apparently poisoned by the Mongols. During Alexander’s early life, independent Russia had three major enemies—encroaching Swedes, Teutonic Knights, and the Mongols.

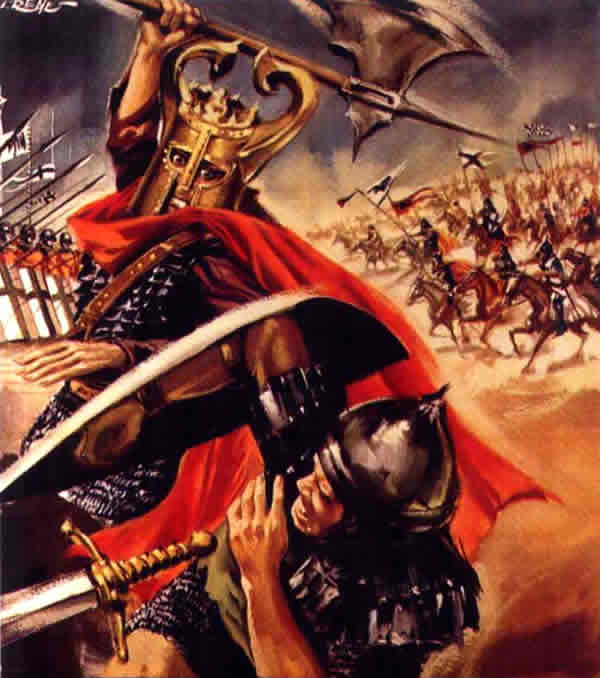

Alexander chose to tolerate, and even collaborate, with the latter but took seriously the threat from the north and west and became a leader in the struggle against both western enemies. He defeated a large Swedish invasion when just 20 years old, and on April 5, 1242, he stopped an even larger invasion by the Teutonic Knights.

The Teutonic Knights were an order first formed during the Third Crusade, similar to the better-known Knights Hospitallers of Saint John, but unlike the latter order, it quickly shifted its attentions to eastern Europe.

|

Initially in connection with privileges granted by King Andrew the II of Hungary (1211), the Teutonic Knights fought against that king’s enemies, the Turkic Quman of the south Russian steppe and nearby areas.

Later (from 1230) it took the lead in fighting against the pagan Russians and then, after the order had absorbed the Livonian Sword Brothers, the Teutonic Knights began to get involved in Russian affairs, acting against the city of Novgorod.

It was in this connection that Alexander, a proven military leader, was recruited by Novgorod to become its prince and fight against the Teutonic enemy. The result was the famous defeat on the ice of Lake Peipus of 1242 in which the invading army was all but destroyed by cleverly positioned and deployed Russians who knew the landscape better than their rivals.

Possibly Alexander had Mongol allies, since archery played an unusual role in the battle. The Teutonic Knights remained a power in eastern Europe but were never a direct threat to Russia in the way that the order was in 1242, so the results of the victory lasted.

Alexander’s young adulthood was disrupted by the reappearance of the Mongols and their conquest of virtually all of Russia. The Mongols had first come into contact with Russian forces on June 16, 1223, during a clash on the Kalka River.

|

| Alexander Nevsky Statue |

In 1237 an even larger Mongol army launched an invasion of Russia. Among the first Russian city-states to fall was Ryazan, in December 1237, followed by Vladimir, in February 1238, and in March 1238, Torzhok, which offered fierce resistance.

By then spring came and the ground was too wet for effective campaigning, but the Mongols returned again, after some campaigning in the steppe against the Turkic peoples during the winter of 1240. Their advance seemed unstoppable and Kiev, the leader of the coalition of princes that was then Russia, was taken on December 6, 1240, ending an era of Russian history.

Pausing to regroup, the Mongols launched a massive and well-coordinated invasion of eastern Europe, masterminded by the Mongolian general Subotai. Only the sudden death of Ogotai Khan (r. 1229–41) stopped the advance, as the interested parties prepared for the power struggle that would accompany the election of a new supreme khan.

|

The election of Mongke Khan (r. 1251–59) quieted things for a while. After his death the Mongols of Russia, known as the Golden Horde, split off permanently from Russia as various parties dueled for supremacy.

At the point that Alexander defeated the invading Teutonic Knights and thereby established, again, his reputation in Russia, the Mongols appeared to be more and more disunified. Alexander was both a mediator and a mitigator, where he could, of the worst abuses of Mongol control.

During the 1240s and early 1250s Alexander, who took his father’s oath of submission seriously, made efforts to appear a loyal vassal of the Mongols and formally acknowledged their power. He continued to enjoy influence with the Mongols and within Russia, one of the reasons he was appointed grand prince in 1252, after the Mongols had deposed his predecessor.

At that time Russia was divided into territories where there was a direct Mongol presence, usually located on the fringes of the Russian cultural area and close to the steppe zone, and territories controlled indirectly by the conquerors. This included Novgorod controlled by Alexander.

It was the Mongol custom to send out tax collectors and other emissaries to canvass the wealth of their territories. First came a census, then generally the appointment of a direct Mongol representative, a basqaq, “the one pressing down,” and finally tax collectors.

It was the presence of these Mongol officers, more than attacks by Mongol armies, that plagued Mongol subordinates in Russia and provoked continued unrest and even outright opposition and rebellion, which always provoked a powerful military response.

During the late 1250s it was Novgorod, still proud from its 1242 victory led by Alexander against the Teutonic Knights, and until then left unassaulted by the Mongols, that was the source of discontent.

Alexander’s actions in quieting it make clear the role he had chosen in Mongol Russia. He made sure that opposition to the Mongols was suppressed, and then Alexander personally sponsored the census taking in Novgorod.

Novgorod paid, and had its pride humbled, but it survived intact (1259). Alexander is also said to have intervened on behalf of the Orthodox Church, to secure its privileges and help prevent Mongol attacks on other cities.

At the time of his death, in 1263, he was still actively engaged in such activities. He was rewarded with sainthood. After Alexander’s death a considerable legend formed, fueled by a vita that presents Alexander as a saintly protector of Russia against the Mongols. He was also associated with some popular uprisings.