|

| Ashikaga Shogunate |

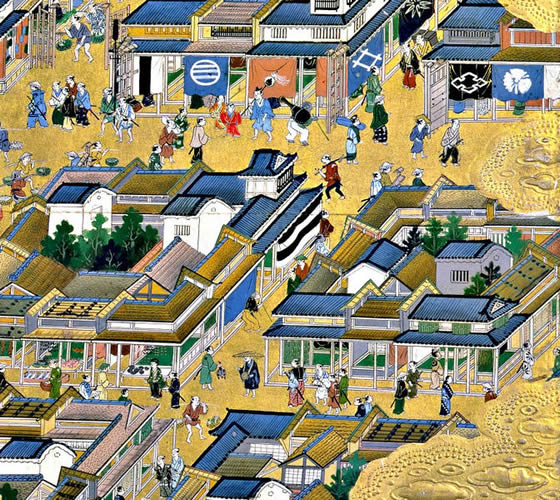

This shogunate saw the Ashikaga family dominate Japanese society, ruling for much of the period from their headquarters in the Muromachi district of Kyoto. As a result the shogunate, or bakufu (“tent government,” in effect a military dictatorship), with military power controlled by the seii tai shogun or shogun (“general who subdues barbarians”)—is called either the Ashikaga or the Muromachi Shogunate.

The Ashikaga Shogunate lasted from 1336 until, officially, 1588, although the last of the family was ousted from Kyoto in 1573, and it did not have much military power after the 1520s. The period when the Ashikaga family dominated Japanese politics reached its peak when Ashikaga Yoshimasa

The Ashikaga was a warrior family that had been prominent in Japanese society since the 12th century, when Yoshiyasu (d. 1157) took as his family name that of their residence in Ashikaga. They trace their ancestry back further to Minamoto Yoshiie

|

Yoshiyasu’s son took an active part in the Taira-Minamoto wars of 1180–85, and six generations later Ashikaga Takauji became the first shogun, from 1338 to 1358. This came about after Emperor Go-Daigo (r. 1318–39) was exiled to the Oki Islands after being accused of plotting against the Kamakura Shogunate that controlled the army. The emperor rallied some loyal forces with the aim of ending the dominance of the Kamakura family.

Ashikaga Takauji

The emperor put his troops under the command of Ashikaga Takauji and sent them to the central provinces. The choice of Takauji was interesting, as he had taken part in plots against the shogunate in 1324 and again seven years later. Put in charge of an army to defeat the enemies of the shogun, Takauji changed sides and decided to support the emperor. He took Kyoto and ousted the shogun, ushering in what became known as the Kemmu Restoration.

|

| Ashikaga Takauji |

However, rivalries quickly broke out between Takauji and another warlord, Nitta Yoshisada. By this time the prestige of the throne was suffering after major administrative failures had clearly resulted in Go-Daigo being unable to protect his supporters. Takauji led his men to Kyoto, which he captured in July 1336, forcing Emperor Go-Daigo to flee to Yoshino in the south.

In 1338 Takauji established what became known as the Ashikaga (or Muromachi) Shogunate, based in Kyoto. Takauji controlled the army and his brother Ashikaga Tadayoshi controlled the bureaucracy, with additional responsibility for the judiciary.

The shogunate initially resulted in a split in the imperial family, with the Kyoto wing supporting it and Go-Daigo and his faction ruling from the southern court at Yoshino. This continued until 1392 when the policy of alternate succession to the throne was reintroduced. After a short period of stability, there was an attempt at an insurrection by Ashikaga Tadayoshi, who seized Kyoto in 1351.

Takauji was able to drive him out, and Tadayoshi fled to Kamakura. Takauji established a “reconciliation,” during which Tadayoshi suddenly died, probably from poisoning. This left Takauji in control of the north, but he died in 1358 and was succeeded by his son Yoshiakira (1330–67), who was shogun until his death in 1367. There was then a short period with no shogun.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu

|

| Ashikaga Yoshimitsu |

When Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358–1408) became shogun in 1369, a position he held until 1395, he was able to develop a system by which families loyal to him held much regional power, and the office of military governor was rotated between the Hosokawa, Hatakeyama, and Shiba families. Yoshimitsu may have been planning to start a new dynasty. This theory comes from the fact that he was no longer administering territory in the name of the sovereign.

Certainly he did try to break the power of the court nobility, occasionally having them publicly perform menial tasks. When he went on long pilgrimages, he took so many nobles with him that the procession, to many onlookers, seemed to resemble an imperial parade. Yoshimitsu was able to build a rapport with Emperor Go-Kogon.

His main achievement, involving considerable diplomatic skill, was to end the Northern and Southern Courts by persuading the southern emperor to return to Kyoto in 1392, ending the schism created during his grandfather’s shogunate.

|

| Emperor Go-Kōgon |

Yoshimitsu also had to deal with two rebellions—the Meitoku Rebellion of Yamana Ujikiyo in 1391–92 and the Oei Rebellion of 1400 led by Ouchi Yoshihiro (1356–1400). Ouchi Yoshihiro had relied on support from pirates who had attacked Korea and also, occasionally, parts of China, but his rebellion came about when he did not want to contribute to the building of a new villa for the shogun.

He had long harbored resentment against the Ashikaga family, and in some ways the villa was merely an excuse for war. However, very quickly Ouchi Yoshihiro was betrayed by people he thought would support him, and after he was killed in battle, the rebellion ended quickly.

In order to ensure an easy succession Yoshimitsu abdicated the office of the shogun to his son Ashikaga Yoshimochi (1386–1428), who was shogun from 1395 to 1423, while he, himself, remained in Kyoto, where he made vast sums of money monopolizing the import of copper needed for the Japanese currency and negotiating a trade agreement with China in 1401.

|

He also created a minor controversy by sending a letter to the Ming emperor of China, which he signed with the title “king of Japan.” In his latter years Yoshimitsu became a prominent patron of the arts, supporting painters, calligraphers, potters, landscape gardeners, and flower arrangers. Many of the artists that Yoshimitsu encouraged became interested in Chinese designs and were influenced by their Chinese contemporaries—this became known as the karayo style.

The system of control established by Yoshimitsu continued under Ashikaga Yoshimochi, and his son Yoshikazu (1407–25), who was shogun from 1423–25. However, it was also a period when the Kanto region of Japan started to move out of the control of the shogunate.

Yoshikazu’s uncle Yoshinori (1394–1441) succeeded him, taking over as shogun in 1428. Yoshinori had been a Buddhist monk from childhood and ended up as leader of the Tendai sect, having to give up the life of a monk when his nephew died. Because of his background, he was determined to establish a better system of justice for the poorer people and overhauled the judiciary.

He also strengthened the shogun’s control of the military, making new appointments of people loyal to the Ashikaga family. Many nobles disliked him because he was seen as aloof and arrogant, and in 1441 a general from Honshu, Akamatsu Mitsusuke, assassinated Yoshinori.

In what became known as the Kakitsu incident, Akamatsu Mitsusuke was hunted down by supporters of the shogunate and was forced to commit suicide. Yoshinori’s oldest son, Yoshikatsu (1434–43), succeeded him and was shogun for only two years. With his death, there was no shogun from 1443 to 1449, when Yoshikatsu’s 13-year-old brother, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, became shogun.

The Onin War

|

| Onin War |

Ashikaga Yoshimasa was born on January 20, 1436, at Kyoto, and when he became shogun, the shogunate was declining in importance with widespread food shortages and people dying of starvation. Yoshimasa was not that interested in politics and devoted most of his life to being a patron of the arts.

He despaired of the political situation, and without any children, when he was 29 years old he named his younger brother, Yoshimi (1439–91), as his successor and prepared for a lavish retirement. However, in 1465 he and his wife, Hino Tomiko, had a son. His wife was adamant that the boy should be the next shogun, and a conflict between supporters of the two sides—that of Yoshimasa’s wife and that of his brother—started in 1467.

Known as the Onin War, most of the fighting took place around Kyoto, where many historical buildings and temples were destroyed and vast tracts of land were devastated. More important, it showed the relative military impotence of the shogun, and the power of the military governors, and quickly changed from being a dynastic squabble to being a proxy war.

It then became a conflict between the two great warlords in western Japan, Yamana Mochitoyo, who supported the wife and infant son, and his son-in-law, Hosokawa Katsumoto, who supported Yoshimi. Both died during the war, and there was no attempt by either side to end the conflict until, finally, exhausted by the 10 years of conflict, in 1477 the fighting came to an end.

|

| Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa |

By this time Yoshimasa, anxious to avoid a difficult succession, had stood down as shogun in 1473 in favor of his son. His son, Yoshihisa, was shogun from 1474 until his own death in 1489, whereupon, to heal the wounds of the Onin War, Yoshimasa named his brother’s son as the next shogun. Yoshimi’s son, Yoshitane (1466–1523), was shogun from 1490 until 1493.

In retirement, Yoshimasa moved to the Higashiyama (Eastern Hills) section of Kyoto, where he built a villa that later became the Ginkakuji (Silver Pavilion). There he developed the Japanese tea ceremony into a complicated series of ritualized steps and was a patron to many artists, potters, and actors. This flowering of the arts became known as the Higashiyama period. Yoshimasa died on January 27, 1490.

From the shogunate of Yoshitane, the family was fast losing its political power. Yoshitane’s cousin Yoshizumi (1480–1511) became shogun from 1495 to 1508 and was succeeded, after a long interregnum, by his son Yoshiharu (1511–50), who became shogun in 1522, aged 11, and remained in that position until 1547.

His son Yoshiteru (1536–65) succeeded him from 1547 to 1565, and, after his murder, was then succeeded by a cousin, Yoshihide (1540–68), who was shogun for less than a year. Yoshiteru’s brother Yoshiaki (1537–97) then became the 15th and last shogun of the Ashikaga family. He had been abbot of a Buddhist monastery at Nara, and when he became shogun renounced his life as a monk and tried to rally his family’s supporters against a sustained attack by Oda Nobunaga.

In early 1573 Nobunaga attacked Kyoto and burned down much of the city. In another attack in August of the same year, he was finally able to drive Yoshiaki from Kyoto. Going into exile, in 1588 Yoshiaki formally abdicated as shogun, allowing Toyotomi Hideyoshi to take over.

He then returned to his life as a Buddhist priest. In at least its last 50 years—and arguably for longer—the shogunate had become ineffective, and warlords had once again emerged, often financing their operations by not only pillaging parts of Japan itself but with piratical raids on outlying parts of Japan and Korea.

The Ashikaga Shogunate remains a controversial period of Japanese history. During the 1930s Takauji was heavily criticized in school textbooks for his disrespect to Emperor Go-Daigo. Many historians now recognize him as the man who brought some degree of stability to the country.

The attitude toward Yoshimasa has also changed. Because he concentrated so heavily on the arts, he neglected running the country. He is now recognized as heading an inept administration that saw great suffering in much of Japan. It would lead to a period of great instability that only came to an end when Tokugawa Ieyasu became shogun in 1603.