|

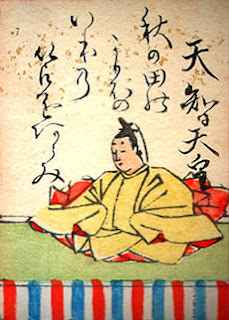

| Tenchi (Tenji) |

Three men ruled as emperor after the coup d’etat until 661, when Emperor Tenchi ascended the throne. He was not formally enthroned until 668, probably because he was preoccupied with a great fear regarding China’s intentions toward his country.

The Tang (T’ang) dynasty in China that Japan so admired and wished to emulate was at its zenith. It had sent strong forces against the states in Korea, subduing Paekche and threatening Koguryo and Silla. Tenchi feared the resurgence of Chinese power in Korea and the impact that might have on Japan.

Even though the Soga clan had been ousted from power, the reforms that Prince Shotoku Taishi, the great Soga regent, had begun were continued after 645. The decades after 645 were called the era of Taika or Great Reforms era, when intense attempts were made to move toward Chinese institutions of government and law.

|

In 645 the future emperor, Tenchi handed over 81 estates and 524 artisans to the emperor, signifying his support of the central government claim that all land belonged to the emperor, as was the practice in China.

Perhaps because of fear of a Chinese invasion Tenchi ordered his brother, the crown prince (later to become Emperor Temmu), to take measures to tighten the central government’s control over the administration and strengthen the army.

He also built Chinese-style palaces for his administration at Otsu, perhaps to be safe in case of a Chinese invasion because Naniwa, the previous administrative center, was near the coast. There are accounts of Tenchi and his courtiers holding Chinese poetry parties at his palace, but none of their works have survived.

Writing poetry in Chinese had become an honored cultural activity. In 668 he ordered his ally in the coup, Fujiwara Katamari, to head a board to compile a set of administrative laws and ceremonial regulations.

Later accounts say that the completed administrative code consisted of 22 volumes, but they have not survived. In 671 he also promulgated a system of ranking for bureaucrats called “cap ranks.”

Other measures Tenchi took to strengthen the authority of the central government included state control of Buddhist priests and temples. Emperor Tenchi’s reign is significant in Japanese history because it represented further advances in Japanese government and culture based on the Chinese model.