|

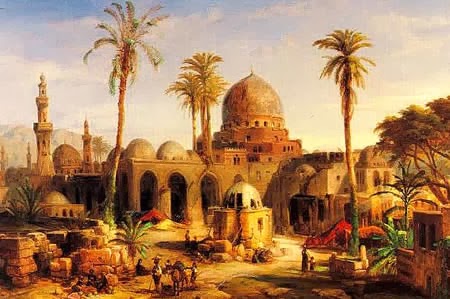

| Baghdad |

The Abbasid dynasty founded the city of Baghdad as a new capital in 762, shortly after the overthrow of the Umayyad dynasty. This shift of the center of power in the Muslim world from Syria toward the Abassid support base in Persia allowed the young dynasty to establish its dominance under the leadership of the caliph, al-Mansur.

However, the move from Syria also saw the caliphate’s influence in Mediterranean affairs decline and rival dynasties emerge as far away as Spain, where the Umayyad dynasty regrouped, and as near as Egypt, from where the Fatimid dynasty dominated much of North Africa from the 10th through the 12th century.

The first two centuries of Baghdad’s history were marked by political strife as the Abassids repressed revolts; the dynasty underwent civil war from 811 to 819. During this civil war the caliph Amin besieged the city. Despite this unrest, Baghdad found itself at the center of a Muslim cultural golden age during these centuries.

|

In the 940s a group of soldiers, the Buyid princes, who had been gaining in strength for a decade, took power in Baghdad; lacking legitimate claim to rule, they become protectors of the caliphate and ruled through Abbasid puppet caliphs.

In 1055 the Seljuk Turk Toghrulbeg came to Baghdad and ultimately relieved the caliph of the Buyid protectorate. Toghrulbeg was named sultan, and the caliph was again reduced to little more than a puppet. But the Seljuk leader’s ambitions led him to rule from outside of Baghdad, visiting only on occasion, and this would give future caliphs at least some small measure of freedom.

The Crusades and internal turmoil challenged the Seljuks’ control of the region, and the caliphs began to challenge their overlords. The breakup of Turkish rule in the late 12th century saw a renewal on a regional scale of the city’s importance, but the city and the region were continually plagued by conflicts between Sunnis and Shi’i.

The Mongols

In faraway Mongolia, warring Turko-Mongol tribes were uniting under the leadership of one man, Temuchin. In 1206 an assembly of tribal nobility awarded him the title Genghis Khan—Universal Ruler. From central Mongolia, Genghis set out on a mission of world conquest.

He immediately began consolidating his power for an attack against the Chinese kingdoms to the south, but full control of China was far off. The Mongols would invade western Asia and establish a dynasty in Iran before they unified China under their rule.

During the early years of Mongol expansion Genghis Khan led armies against the sultan Ala ad-Din Muhammad, Khwarazm Shah, as a punishment for his challenge to Mongol authority in the region of Central Asia. Genghis’s punishment of the Persian leader helped establish a reputation for Mongol brutality.

The caliph in Baghdad, al-Nasr, felt threatened by the onslaught against Sultan Muhammad and appealed to the Ayyubids in Syria for aid. The Ayyubids were battling the crusaders and did not send aid, but the threat of Genghis Khan never materialized. Genghis died in 1227, and Ogotai Khan, his son, succeeded him.

In 1232 Mongol forces had penetrated as far as Azerbaijan, and the caliph annexed Arbela in Upper Mesopotamia, possibly as a defensive measure. In 1236 the caliph mobilized his armies against the Mongols, who were moving south into Upper Mesopotamia, and in 1238 the caliph went to Baghdad’s great mosque and called for holy war against the invaders.

This time Ayyubid reinforcements arrived, but the ensuing battle was a defeat for the caliph. The Mongols withdrew deep into Persia, and terms were reached, though raids into Mesopotamia continued with accounts of the period reporting various Mongol harassments of Baghdad.

The Mongol conquest of the Middle East began during the reign of Mongke Khan. In 1252 Mongke dispatched his brother Hulagu Khan to take control of the region. Some sources suggest that the arrival of Hulagu in Azerbaijan was instigated by a mission by the Qadi of Qazvin, in an attempt to subdue the Isma’ilis, known as the Assassins for their frequent tactic of the same name.

The Isma’ilis operated from their stronghold in the mountainous region of northern Iran. The repression of the Isma’ilis was one of Hulagu’s first goals. Hulagu dispatched Baichu to the west to repress the Seljuk’s in Rum, and in 1256 Mongol forces defeated the sultan and recognized his younger brother, establishing Mongol overlordship of Rum. In the same year, the Mongols completed their mission against the Isma’ilis, destroying the last of their mountain strongholds and executing their leader, Khurshah.

Having secured his base and the vicinity to its west, Hulagu focused his attention on the caliphate in Baghdad. Hulagu sought to dominate both Baghdad and its caliph, despite their dramatic decline in prestige. The court of the caliph, al-Musta‘sim, was divided over how to respond.

The caliph, presented with an ultimatum, could surrender—saving his life, his position, and his city—or resist. Indecision left al-Musta‘sim largely unprepared for the onslaught that would follow his disregard and disrespect of Hulagu and his armies. The Mongol forces besieged the city for several weeks before storming it on February 6, 1258.

The damage to the city was extensive. Al-Musta‘sim, his sons, and much of their entourage were killed; as it was against Mongol belief to shed royal blood on the ground, the caliph was rolled into a carpet and trampled to death by horses. Al-Musta‘sim was the last Abbasid caliph of Baghdad.

From Baghdad, Hulagu’s forces moved into northern Syria, taking Aleppo in January of 1260. The Ayyubid ruler in Damascus, An-Nasir Yusuf, fled his capital, and the city surrendered to Hulagu’s general Kitbuqa. Hebron, Jerusalem, and Ashkalon were raided, and various Ayyubid princes submitted to the invaders. Again, much of the Mongol army was unilaterally withdrawn to Azerbaijan, where Maragheh was chosen as the capital of the new Il-Khanate (one of four khanates of the Mongol Empire).

The Ayyubids’s conquest by the Mongols marked the end of their dynasty, as they had already been replaced in Egypt by the Mamluk dynasty. General Kitbuqa remained to solidify the new conquests in Syria, while Hulagu became embroiled in the Mongol succession crisis and began to battle the Golden Horde to his north.

In the eastern Mediterranean region the crusaders in Jerusalem were not prepared to surrender to the Mongols and issued calls for reinforcements to the western European kingdoms, while they temporarily tried to appease Kitbuqa. When the crusaders did not dismantle their fortresses, however, Kitbuqa retaliated, sacking Sidon in August 1260.

The crusaders responded by allowing the Mamluks of Egypt to dispatch troops through their territory and even provided the Muslim forces with supplies to battle the Mongols. In September 1260 the Egyptian army defeated the Mongols in Galilee, and Kitbuqa was either killed in the battle or executed after his defeat.

The Il-Khanid Mongols retreated beyond the Euphrates to their power base. Within the Il-Khanate, Hulagu and his son Abaqa would enjoy stability despite threats at the border. The Il-Khanids continued to work diplomatically against their Mamluk enemies in Syria, at times approaching the crusaders to propose coordinated attacks.

In 1299 Ghazan Khan, a Muslim convert, attacked the Mamluk forces, which retreated to Egypt in defeat. Syria and Palestine were briefly reoccupied until Ghazan withdrew to Mesopotamia, and it was not until 1320 that the Mongols made peace with the Mamluks. After the death of Abu Sa‘id in 1235, the Il-Khanate disintegrated into rival, mostly non-Mongol, dynasties.

The Mongol leader Timurlane emerged as a great force in the region at the end of the 14th century, regaining Mongol control of Persia and doing battle as far east as the Ottoman Empire. But Timurlane’s death in 1405 saw the Mongolian empire in Persia again disintegrate and effectively ended Mongolian influence in the region of the Middle East.

The immediate and lasting effects of the Mongols in the Middle East are varied in degree. The Mongol conquest of Hulagu ended two institutions of Islamic rule, finally ending the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad and Ayyubid dynasty, the realm of which was already confined to Syria and parts of Palestine. This allowed Mamluk rule to fill the power vacuum.

A century and a half later that power vacuum would be re-created by Timurlane’s temporary conquests and the subsequent disintegration of Mongol rule in the Middle East following his death, only to be filled by the Ottomans. Culturally, the impact of the Mongols was minimal, with the exception of Persia, to which area their lasting presence in western Asia was confined. It is in the period of the Il-Khanate that the greatest impact of far eastern culture on Persia is witnessed.