|

| Tudor Dynasty |

The Tudor dynasty includes the reigns of the following monarchs: Henry VII (1485–1509), Henry VIII (1509–47), Edward VI (1547–53), Queen Mary I (1553–58), and Elizabeth I (1558–1603).

The Tudor dynasty began with the clandestine marriage between Owen Tudor and Catherine of Valois and continued the Plantagenet line, although in a much modified form. This marriage produced a son, Edmund Tudor, who was made 13th earl of Richmond in 1453. His son, Henry, was eventually crowned Henry VII after his victory at the Battle of Bosworth, ending the Wars of the Roses and bringing the Tudors to power.

The Tudor dynasty, spanning from Henry VII’s reign in 1485 to the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, served as the catalyst for England’s maturation from a weak country in the Middle Ages into a powerful Renaissance state and encompassed some of the most dynamic and progressive changes in English history.

|

Although marked by intermittent religious strife, this dynasty also brought the restructure of English society, the spread of capitalism, intellectual and cultural advancements, the Protestant Reformation, economic stability, the growth of nationalism, the beginnings of the Renaissance, and the birth of the Church of England.

The 15th and the 16th centuries were a watershed time in English history because of a multitude of events, and the Tudor dynasty played a crucial part within the larger scope of both English and world history.

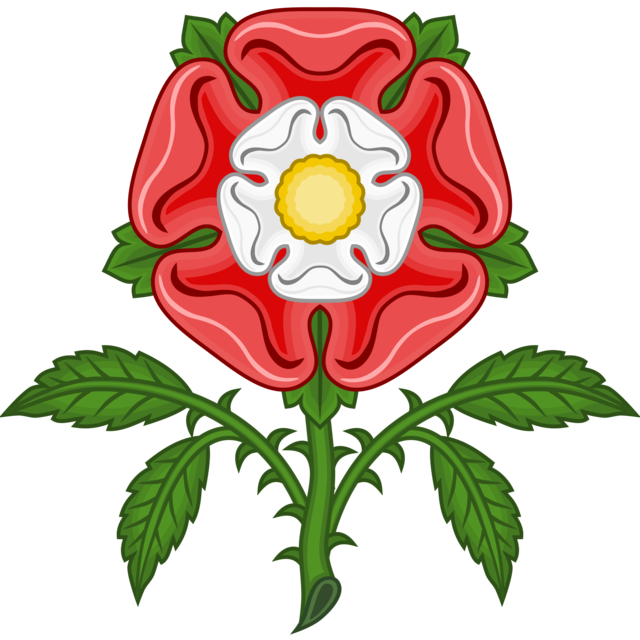

The dynasty’s symbol, the Tudor rose, combined the red and white roses of the Lancastrian and Yorkist Houses and symbolized the union of the two factions, which was cemented by Henry VII in January 1486 when he married Elizabeth of York, eldest daughter of Edward IV. The Tudors began their rule among bloodshed and treason but left England a more peaceful and confident nation.

|

| Tudor rose |

As Henry VII claimed the throne of England, he was acutely aware that his succession was not absolute. Although pretenders attempted to stake claim to the throne during his rule, Henry VII managed to remain in power. His son, Henry VIII, succeeded him with no dispute regarding his right to rule.

Henry VIII’s reign was highlighted by his necessity to secure the Tudors’ claim to the throne through a male heir and is remembered for his wives. He married six times, producing one son and two daughters. After Henry VIII’s death, his young and feeble son Edward VI ascended to the throne and ruled for a short time, dying of tuberculosis at 15 years old.

Before Edward VI died, he named Lady Jane Grey, who married the duke of Northumberland’s son, as heir to the English throne. She ruled for nine days until she was deposed by Mary I, imprisoned, and eventually executed.

|

Queen Mary’s rule was punctuated by her insistence on reinstating Catholicism and her quest to have a child. A devout Catholic and wife of philip of Spain, Mary returned England to Catholicism after the Protestant reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, reinstated the heresy laws, and commenced with burning Protestant bishops and others at the stake.

This violent act only served to rally more Englishmen to adopt the Protestant faith. At two different times Mary believed she was pregnant; however, she bore no children. Her signs of pregnancy, a swollen stomach and nausea, were believed to be either a stomach or an ovarian tumor, and she eventually died in 1558, after naming Elizabeth heir to the throne.

Elizabeth I, the last of the Tudors, found England in disarray when she ascended the throne in 1558. Her 44-year rule provided her with the longevity and the ability to solidify England’s dominance in world affairs through its development of a formidable navy that eventually defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588.

By the end of her rule, religious strife had largely dissipated. The Crown possessed absolute supremacy over Parliament, but the two operated in relative cooperation. She refused to marry throughout her life, although she was inundated with marriage proposals from numerous suitors. Hours before she died, Elizabeth named James VI of Scotland to succeed her, ending the Tudor rule and ushering in James I of England and the Stuart dynasty.

Tudor monarchs were known as politically gifted and quite charismatic; these traits were reflected in the years that they ruled. Henry VIII and Elizabeth I most accurately embodied these characteristics within their respective rules. As Henry VIII struggled to produce a male heir, he created the Church of England and was made both political and religious leader of England with the Act of Supremacy (1534).

The Church of England was established by 1536, but its power and future were severely threatened by Mary’s reign. The Elizabethan Religious Settlement, drafted in two parliamentary acts, deftly settled this continuing religious feud. The Act of Supremacy (1559) reestablished the Church of England’s independence from Rome.

The Act of Uniformity (1559) set the order of worship to be used in the English Book of Common Prayer and required every man to attend church once a week or face a monetary fine. The Tudor dynasty changed England from a disjointed nation into a cohesive international power.