|

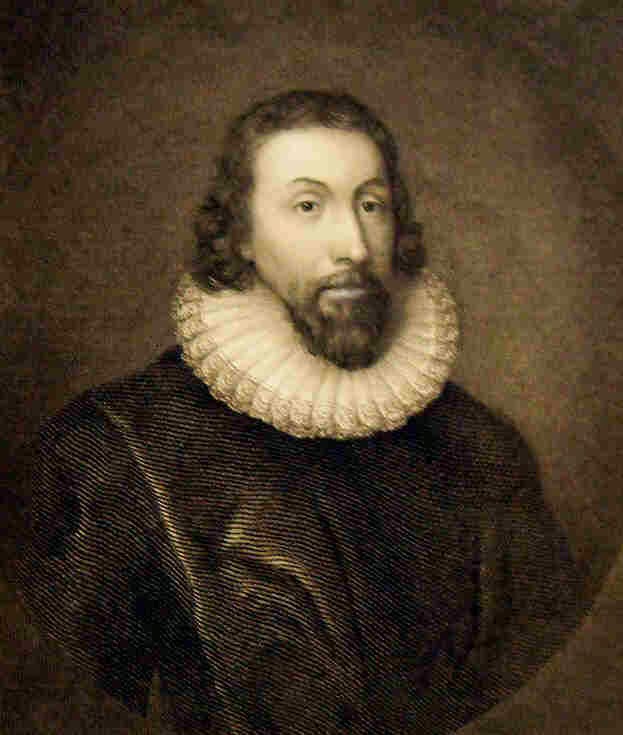

| John Winthrop |

John Winthrop was born in January 1588 in Suffolk County, England, the only son of a prosperous landowner. He studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, but did not earn a degree. By family arrangement, he married at 17 and devoted himself to managing family estates.

He also studied law and was admitted to Gray’s in 1613. He became a justice of the peace in 1617 and appointed an attorney in the Court of Wards in 1627, by which time he had become an ardent Puritan.

Beset with a large family to provide for, troubled by the widespread corruption of the Court of Wards, and deeply disturbed by the government’s religious and political practices, he threw in his lot with the fledgling Massachusetts Bay Company.

|

When the company agreed to turn control of itself over to the residents of the colony it was about to establish, Winthrop agreed to be one of those residents, and the company elected him governor. He sailed in April 1630, leaving many of his family in England.

Winthrop set the character of early Massachusetts in a sermon preached on board the Arabella. In that sermon, he argued that the colony would be created as a covenant with God with civil and ecclesiastical power consolidated in the hands of the colony’s leaders.

He devoted his political life, both in and out of office, to that principle. He also maintained that Massachusetts should be “a city upon a hill,” chosen by God to serve as an example to England of what God intended for his people.

Despite his best efforts, Massachusetts was not the docile, benign autocracy Winthrop had envisioned. The individualistic Roger Williams, with his separatism and his attacks on both the colony’s ownership of its land and its claim to enforce religious conformity, was a sore trial for Winthrop.

Although Winthrop liked Williams personally, he understood that Williams’s continued residence in Massachusetts was detrimental to the future of the colony and supported his banishment in 1635. No sooner than the Williams affair had been settled, Winthrop had to deal with a similarly destructive issue in the antinomian crisis surrounding Anne Hutchinson.

Hutchinson’s view that salvation was gained only through God’s grace, and not through the performance of works, challenged clerical leadership and church discipline and had unacceptable implications for social order and the authority of the established government. Perhaps because she was a woman, he showed far less consideration for her than he had for Williams when she was banished from the colony and later excommunicated from her church.

In both cases, Winthrop certainly showed no sympathy toward those who had challenged the colony’s mission, but his goal was the survival of the colony, and in this he did what he believed to be necessary. He remained active in the life of the colony after these confrontations, serving as governor, deputy governor, magistrate, and diplomat in negotiating the formation of the United Colonies in 1644. He was its first president.

His History of New England, 1630–1649 is a major source for the early history of both Massachusetts and New England. It reveals little about Winthrop’s personal life, but it does show a man who put the greater good of his colony’s survival above all else.