|

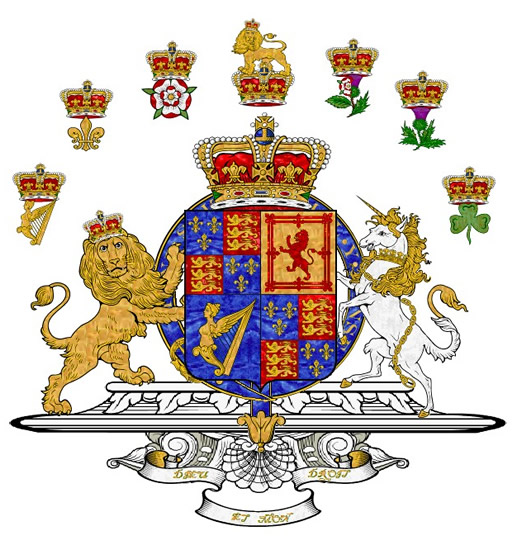

| House of Stuart (England) |

The Stuart dynasty ruled England at a time when the power of the absolute monarchy was declining in England and the powers of representative government were increasing.

The Stuart dynasty came into power in England with the death of the last Tudor dynasty, Queen Elizabeth I, in 1603. Elizabeth died without an heir, forcing the English government to ask the Stuart family of Scotland to assume the throne of England.

The Stuarts were related to the House of Tudor, as Mary Stuart and Elizabeth were cousins. Despite the fact that Mary was executed for treason in 1587, her son James Stuart (James I), the king of Scotland, was chosen to succeed Elizabeth. This choice brought the Crowns of Scotland and England under one monarch, despite the fact that they remained two separate kingdoms.

|

James was a firm believer in the powers of an absolute monarch, as is evidenced by his writings and speeches to the English parliament. When James came to the throne of England, he had to contend with financial difficulties and clashes with Parliament over the prerogatives of the monarchy.

These issues arose as James attempted to raise new revenues by imposing taxes on his subjects without the approval of Parliament. James was also upset by the fact Parliament was against his choice of a potential bride for his son because she was Catholic and Spanish. This hostility occurred as a result of the tensions between Protestant England and Catholic Spain.

James was so infuriated by the Parliament’s creation of the Great Protestation in 1621, a list of privileges the English parliament claimed it was entitled to, that he dissolved Parliament and arrested four individuals responsible for this action.

Charles I succeeded his father to the thrones of Scotland and England when James died in 1625. Parliament continued to attempt to place restrictions on the power of the king by issuing a Petition of Rights in 1628.

The petition placed limitations on the king’s power to raise revenue without the permission of Parliament, required the permission of subjects to house soldiers in their homes, placed restrictions on the king to impose martial law, and restricted the king from arresting a subject without laying proper criminal charges.

Charles signed this petition because he wished to obtain funds from Parliament, but he soon illustrated his desire to subvert the petition by acquiring as much money from his subjects as possible without assembling Parliament through the extension of existing taxes.

The attempt by Charles I to rule England without the assent of Parliament caused many problems and violated the traditional institutional basis of English law. Charles also made many enemies by imposing Anglican conformity on the populace and taking away the pulpits of the Puritans.

Dissolution and Recall of Parliment

It was the desire of the archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, to impose Anglican conformity on the Presbyterian Scots that led to the English Civil War. Charles prepared to move an army into Scotland in 1638 to create a settlement to this religious dispute with the Scots.

Charles could not afford this army, and Parliament refused to give Charles any more money unless he rectified the grievances that had occurred during his and his father’s reigns. Charles refused to accept this ultimatum and dissolved Parliament in May 1640, but he was forced to recall Parliament as he needed funds to subdue the Scottish army.

When Parliament was assembled in October 1641, it attempted to place further restrictions on the ability of the king to raise revenue and stipulated the abolishment of certain administrative courts. Parliament also demanded the king to convene Parliament every three years and commanded Charles to remove certain individuals from power.

This last demand eventually led to the execution of Laud and one of Charles’s councilors, Thomas Wentworth, the earl of Strafford. Charles attempted to intimidate Parliament by ordering the imprisonment of five individuals who held influence in the House of Commons, but they fled. Charles chose to take drastic measures against Parliament and assembled an army at Nottingham in 1642, leading to the start of the English Civil War.

English Civil War

|

| Victory of the Parliamentarian New Model Army, under Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, over the Royalist army, commanded by Prince Rupert, at the Battle of Naseby (June 14, 1645) |

The English Civil War lasted from 1642 to 1649, as the Stuart cause gained a lot of support from the northern and western sections of England and the rural areas. The parliamentary forces possessed a great deal of support from southern and eastern England certain urbanized areas of the country.

A Puritan named Oliver Cromwell was instrumental to the parliamentary cause as his armies won important victories at Marston Moor in 1644 and Naseby in 1645 and forced Charles to flee to the Scots for assistance.

This move by Charles was disastrous as the Scots handed him over to the parliamentary forces in exchange for 400,000 pounds. A debate ensued in regard to the future of Charles and the English political system. While this debate raged, a Scottish army was assembled in support of Charles but was quickly defeated. This gave the radicals another excuse to preside over a trial of Charles, which found him guilty and executed him on January 30, 1649.

|

The king’s son, Charles II, attempted to restore his family’s claim to the English and Scottish thrones by allying with the Scots. Charles II won Scottish support by guaranteeing the Scottish Kirk (church) instead of imposing Anglican conformity, but his army was defeated, forcing him to flee to the continent.

Following the English Civil War, Cromwell used his influence in the army and English politics to take control of the English government by assuming the position of Lord Protector. The death of Cromwell in 1658 and the subsequent political problems the English faced were enough for Parliament to seek a restoration of the Stuart monarch in 1660.

Charles II returned to England but had to accept the limitations imposed on royal authority by the English parliament. Anglicanism was made the official religion of England and Ireland, but Scotland was allowed to retain their Presbyterian Kirk.

The major problem concerning the return of the Stuart dynasty to the English throne was the Stuart family’s Catholic leanings. Charles II was influenced by the French court and his French mother, and in 1670, he allied with Louis XIV, king of France, against the Dutch. This agreement also stipulated Charles II would proclaim himself a Catholic when the tensions between Catholicism and Protestantism diminished in England.

This agreement was a successful move in regard to foreign policy for this victory against the Dutch allowed the English to acquire the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam and confirmed the superiority of English naval power over the Dutch.

Charles II died in 1685 without leaving any legitimate heirs to succeed him, causing his Catholic brother James II to ascend the thrones of England and Scotland. The accession of James II concerned some members of Parliament for they feared a Catholic monarch would stay on the throne of England for some time. James II compounded this fear by making it legal for Catholics to hold governmental positions in 1687.

It is impossible to determine whether he sought to restore the absolute powers of the monarchy, but he intended to bring Catholicism back to England. This concern over a Catholic monarch became particularly acute when James II had a son in 1688, who would certainly be raised in the Catholic faith.

The Whigs and a number of Tories engineered a plan to remove James II by inviting James II’s daughter Mary, who was Protestant, and her husband, William of Orange, to invade England and seize the English throne. William, who was looking for English support against the French, agreed to this and went ashore at Torbay on November 5, 1688, with an army numbering approximately 14,000 soldiers.

Support for James II dwindled as the English gentry and populace wanted a Protestant heir to assume the throne after James II died. This lack of support forced James II to flee to France, thereby forfeiting the Stuart claim to the English and Scottish Crowns.