|

| Mehmed I |

Yet, at the moment of victory, one of Lazar’s lieutenants, Miloš Obilic, approached him, pretending that he was defecting to the Ottoman. Instead he stabbed the sultan dead. Lazar was soon captured and decapitated in Murad’s tent.

After the death of Murad on the battlefield of Kosovo, where 600 years later Serb leader Slobodan Miloševic would ignite the spirit of Serb nationalism and begin a new series of Balkan wars, Murad’s son Bayezid I became sultan.

Bayezid was an energetic warrior, determined to build on the patrimony of his father, Murad. He earned the nickname of Yilderim, “Lightning,” for the speed and decisiveness of his movements.

|

In the First World War when Turkey was an ally of imperial Germany, an elite division trained by General Liman von Sanders and other German advisers would become known as the “Yilderim Division.”

In 1396 armies from Christian Europe gathered for a crusade to save Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine, or Eastern Roman, Empire, from its growing encirclement by the Ottomans.

However at Nicopolis, the impetuosity of the French knights, which had doomed them in 1346 and 1356 fighting the English at Crécy and Poitiers, and would also lead to their defeat by the English archers again at Agincourt in 1415, gave Bayezid an opening in which he was able to destroy the entire Christian army.

As Lord Kinross wrote in The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire, “the finest flower of European chivalry lay dead on the field of Nicopolis or captive in the hands of the Turks.”

Siege of Constantinople

Two years earlier in 1494 Bayezid had already begun his siege of Constantinople, also called Byzantium. But its ancient walls, combined with some help brought to Emperor Manuel II Palaeologus by the French Marshal Jean Boucicaut, who had survived the slaughter at Nicopolis, enabled Constantinople to withstand Bayezid’s siege. A final assault by some 10,000 Ottomans, most likely from the elite Janissary, or yeni cheri, corps, ended in defeat.

However Bayezid was determined to try another assault on the city when an even greater threat loomed from the east. For several years Bayezid had been involved in a cold war with the Turkish warlord Timurlane (Tamerlane), or Timur the Lame, who was carving out with his sword a vast empire in Central Asia.

Finally taunting words between the two warrior sultans led to open warfare in 1399, when an expedition led by Bayezid’s son Suleiman captured one of Timurlane’s vassals, Kara Yussuf, and took him prisoner.

|

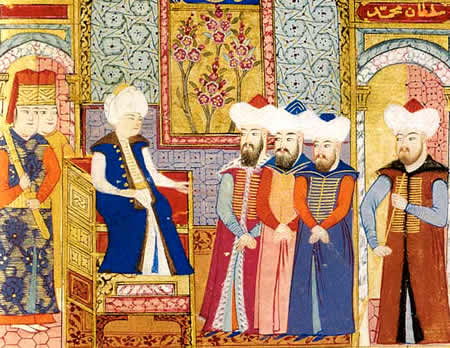

| Mehmed I court |

Timurlane immediately struck back and took the Ottoman-ruled town of Sivas, burying alive thousands of its citizens. A sudden paralysis seized Bayezid, who did nothing in return. Emboldened by his rival’s lack of action, in 1402 Timurlane invaded the heartland of the growing Ottoman Empire, Anatolia.

There on July 28, 1402, the two great Eastern armies met at Ankara, with Bayezid’s 85,000 troops, according to Finkel, outnumbered by the 140,000 of Timurlane. It appears that Bayezid felt his Janissaries could win the day for him, and he positioned himself at their head in the center of the Ottoman army.

Suleiman commanded the left wing, as Kinross relates, while the Serbian ruler Stephen Lazarevitch led the right. Mehmed, Bayezid’s favorite son, commanded the rear. By virtue of his position of command, the year of Mehmed’s birth seems in question.

|

If he was born in 1389, it is unlikely that Bayezid would have entrusted such a command to a prince who was only 13 years old at the time. The battle, which Bayezid had all hopes of winning, turned into a disastrous defeat for the Ottomans.

Some of the Anatolian princes, newly conquered by the Ottomans, simply failed to fight for him. Timurlane took Bayezid alive. Although some stories claimed Timurlane exhibited the captured sultan in a cage, these seem fanciful by modern accounts.

Justin Marozzi in his Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conquerer of the World, quotes Timurlane’s chronicler Sharaf addin Ali Yazdi that Timurlane actually had intended to restore Bayezid to his throne. Wrote Yazdi, Timurlane “had resolved ... to raise the dejected spirit of Bayazid by reestablishing him on the throne with greater power and magnificence than he had enjoyed before.”

If Yazdi was accurate, Timurlane may have felt that it was better to have an Ottoman sultan on the throne, in his debt, than another who would be hungering for revenge. But what is true is that in 1403, Bayezid did die, either by his own hand or by natural causes. Ironically his great conqueror, Timurlane, died two years later in 1405, while planning the conquest of China.

Civil War

The capture and subsequent death of Bayezid set in motion a complex civil war, in which his sons struggled for his power. Amazingly Christian Europe, perhaps still remembering the disaster at Nicopolis, did little to exploit this interregnum to deliver what could have been a decisive blow upon the chaotic Ottoman realm.

Timurlane, according to Marozzi, actually made one of the first moves. After assuring, in Yazdi’s words, that Bayezid would be buried “with all the pomp and magnificence” due a ruler of his rank, Timurlane paid a surprise visit to Bayezid’s son, Musa Çelebi, who, Marozzi notes, received from the conqueror “a royal vest, a fine belt, a sword, and an [arrow] quiver inlaind with precious stones, thirty horses, and a quantity of gold.” Apparently, before his death, Timurlane had the idea of grooming Musa to take his father’s place.

Musa was given to the wardenship of the emir of Germiyan, who later handed him over to Bayezid’s son Mehmed, who had retreated to north-central Anatolia, where Timurlane left him in peace.

In fact Timurlane seems to have determined that whoever inherited Bayezid’s throne would be in his debt. In fact according to the online Encyclopedia of the Orient, in the entry for Mehmed I Çelebi, it notes, “1403: Following the death of Bayezid I, Timur Lenk divided the defeated Ottoman empire between 3 of Bayezid’s sons, Murad in Amasya (center of today’s Turkey), Isa in Bursa (western Turkey) and Süleyman in Rumelia (Balkans).” Nevertheless in 1404–05, Mehmed defeated Isa and took Bursa for his own. (However, Finkel states that Isa was killed by Suleiman in 1403.)

After Ankara, Timurlane did not pursue Suleiman, when he withdrew to the west in the Turkish part of the Balkans, Rumelia, where he established his own realm among the Balkan Christians, counting more on their loyalty than that of the Muslims of Anatolia.

At the same time Suleiman ended with the Treaty of Gelibolu in 1403 the state of war that had existed been Constantinople and the Ottomans since Bayezid had begun his siege of the city in 1494.

Indeed the diplomatic alliances between Christians and Muslims in the Balkans 700 years ago stand in stark contrast to what today is being called a “clash of civilizations” by some in both religious camps.

Prince Suleiman, in fact, felt so secure with his Christian alliances in the Balkans that in 1404 he crossed the Dardanelles to attack his own brother Mehmed in his small kingdom in Anatolia. Mehmed was forced to retreat before his brother, who may have brought some of his Serb or other Christian allies to strengthen his army.

In 1409, however, as Finkel writes, Prince Musa staged a surprise attack on Suleiman by crossing over from Anatolia into Rumelia. Mircea, the voivode, or prince, of Wallachia, formed an alliance with Musa, affirmed through the marriage of Mircea’s daughter to Musa, and joined in the attack on Suleiman.

Mircea, in fact, was the grandfather of the historical Dracula, Vlad the Impaler, who would also rule as voivode of Wallachia, although he was born in Transylvania, then part of Hungary. Musa proved a more competent warrior and soon captured in 1410 much of the land Suleiman had seized in the Balkans, including the city of Edirne.

In 1411 at Musa’s orders, Suleiman was executed, removing one candidate for the throne. He was strangled, most likely with a traditional silken scarf, in keeping with the Ottoman taboo about shedding royal Ottoman blood when a member of the dynasty was executed.

With Musa now ruling Suleiman’s domains as well as his own, the other forces in the civil war, the Byzantine emperor Manuel II, the Serb Stephen Lazarevich, began to see Musa as a greater threat than was Mehmed. Consequently they threw their support to Mehmed, which was in large degree due to Musa’s own fault.

Musa broke the treaty of 1403 with Constantinople by attacking the city in 1411, when Suleiman’s son, Orhan, as Finkel writes, had taken refuge with the emperor. In 1413 Musa would capture Orhan but for some reason released him. In spite of this act of mercy, the civil war continued.

New Alliances

In a daring move Mehmed entered into a new alliance with Emperor Manuel II to gain his support against his brother, Musa. In 1412 envoys of Manuel had sealed the pact with Mehmed at his Anatolian capital at Bursa.

With the Byzantine navy still the strongest fleet in the eastern Mediterranean, Manuel offered it to Stephen and Mehmed to convey soldiers and supplies for the coming campaign against Musa, which would be fought in Europe, not Turkey.

Each Byzantine ship was able to fire the feared “Greek fire,” at enemy ships, a flammable substance that, as napalm today, would start a blaze that virtually nothing could extinguish.

In 1412 supported by the Byzantines and the Serbs, Mehmed met Musa at Camurlu in Serbia on July 5, 1413, and won a smashing victory. After his triumph Mehmed had Musa strangled in his turn. After his victory Mehmed remained true to his treaty with Emperor Manuel.

John Julius Norwich quotes him in A Short History of Byzantium as sending this message to Manuel: “Go and say to my father the Emperor of the Romans that from this day forth I am and shall be his subject, as a son to his father. Let him but command me to do his bidding, and I shall with the greatest of pleasure execute his wishes as his servant.”

In 1413 Mehmed was officially enthroned as Sultan Mehmed I. For the remainder of his life, Mehmed remained true to the pact he made with Manuel II. He now attempted to make peace with some of the Anatolian nobles who had supported Musa or Suleiman against him in the civil war. A large number had supported him from the beginning; the others he now sought as allies.

Two years later in 1415, Mehmed faced a revolt led by either his brother, Mustapha, who apparently had been killed at the Battle of Ankara in 1403, or by a very convincing imposter.

Mustafa, in fact, began negotiations with Emperor Manuel and with the ruling doge of Venice. Sensing a real threat, Mehmed struck at Mustafa and at Cuneyd of Aydin, an Anatolian noble who turned against him after he had first made peace.

Mehmed quickly defeated the two of them and, when they sought sanctuary in the Greek city of Thessalonica, Manuel remained true to his treaty with Mehmed and imprisoned them both. Mustafa was imprisoned on the island of Lesbos.

Mysticism

Yet still there was no peace for Mehmed, who could now justifiably be referred to as Mehmed I. Just as the dynastic struggle within his own family seemed to have come to an end, he was faced with an uprising by the Islamic mystic Sheikh Bedreddin in 1416. The sheikh threatened to become a rallying point for all who were still disaffected with Mehmed’s rule; thus it was imperative he strike decisively.

Mysticism, especially Sufism, had a wide, if secretive, following in the Ottoman Empire, and Mehmed could not risk the sheikh’s preaching a religious jihad, or holy war, against his rule. Mehmed swiftly attacked Sheikh Bedreddin, who was unceremoniously put to death in the marketplace at Serres.

Because Mircea of Wallachia had apparently leaned toward Bedreddin, if only to gain greater freedom from central Ottoman rule, Mehmed required hostages from him for his good behavior. As Finkel observes, “One of these boys was Vlad Drakul, later known as the ‘Impaler.’” Indeed it was from the Turks that Vlad learned the punishment of impaling. In 1416, Mehmed made Wallachia a formal vassal state of the Ottoman Empire.

For five years Mehmed governed with little opposition to his rule. Removed from the need of carrying on far-flung wars, he established himself as a patron of the arts and a great builder. On May 26, 1421, Mehmed I died in Edirne. However he was buried in Bursa, in the Anatolian heartland of his Ottoman Empire.