|

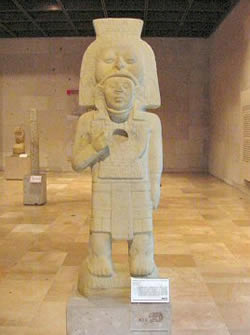

| Huaxteca |

Although Eckholm later modified his point of view, his fieldwork established that the Huastecans had “developed in a wide area that extends without precise boundaries through the actual states of Tamaulipas, northern Veracruz, San Luis Potosí, Hidalgo, and some parts of Queretaro and Puebla.

Realizing that there were abundant archaeological sites and materials in the region that had been neglected,” Eckholm developed a timeline that showed that the Huastecans had developed a flourishing culture, which began sometime in the early Christian era.

The Huastecans appear to be descended from the Mayans and became isolated in their region around the year 100 by stronger peoples, the Nahuas and the Totonacs. Ake Hultkrantz advanced the thesis in his The Religion of The American Indians that all Mayans, including the Huastecans, “spread from Huehuetenango in northwestern Guatemala, where a corn-farming community was in existence as early as 2600 b.c.e.”

In this enforced exile from their Mayan homeland (possibly among the Mayans of the Yucatán peninsula in Mexico), their language developed its own character. The Mexican archaeologist Lorenzo Ochoa felt that the Huastecans eventually broke out of their insularity and established contacts with the dominant cultures of Mexico.

The Preclassical period of Mexican history is considered to have existed from 2000 b.c.e. to 300 c.e., the Classical period from 300 c.e. to 900 c.e., and the Postclassic from 900 c.e. to 1520 c.e., the year before Cortés crushed the last major indigenous kingdom, the Aztec Empire, thus ending the independent rule of Mexicans.

Some of the Huastecan centers identified by Eckholm were at Las Flores, Tampico, Pánuco, Tuxpan, Tajin, and Tabuco. Unique among cultures like the Toltec, Mayan, and Aztec famed for their use of rectangles and squares, the Huastecans built oval structures, like their temple at Las Flores. Eckholm advanced the thesis that the cult of Quetzalcoatl actually began among the ancient Huastecans.

The Huastecans, as with other Mesoamerican peoples, used the bow and perhaps the sharp obsidian-edged sword used by Aztecs in warfare. Mesoamerican warriors also used the atlatl, or spear-thrower, which was used to add great range to darts that they fired with its aid.

Shields, often brightly covered with bird feathers, were also a common feature among Mesoamerican armies. Hassig observes, “The use of body paint in warfare extended throughout Mesoamerica and was practiced inter alia by Mayans, Tlaxcaltecs, Huaxtec, and Aztecs.” Among the Aztecs at least, wrote Hassig, “the use of special face paint was a sign of martial accomplishment.”

The Aztecs had emerged by the 15th century as not only the dominant warriors of Mexico, but were also renowned for their trading ability. This, of course, evoked jealousy among the other kingdoms of Mexico. The Gulf Coast of Mexico where the Huastecans lived, known to the Aztecs as the “hot lands,” was a natural target for Aztec merchants. In 1458 Huastecans murdered Aztec merchants in Tziccoac and Tuxpan.

In revenge, the Aztec emperor Moctezuma I launched a campaign to punish the Huastecans. It also gave the Aztecs a cause to conquer some of the richest lands in Mexico. As Peter G. Tsouras writes in Warlords of the Ancient Americas, the region produced “cotton, brilliant feathers, and jewels, and ocean products such as various prized shells, and exotic foods like chocolate and vanilla.”

The Huastecans, like the Aztecs, were a warrior people, and the Aztecs were wary of the encounter. For one thing, their military strategists were not familiar with the geography of the Gulf Coast area. To bolster the spirits of the Aztec army, Tsouras notes, on the eve of the battle with the Huastecans, an Aztec captain declared to the soldiers, “Contemplate your death and think of nothing else. You have come here to conquer or die since this is your mission in life.” Moctezuma I decided to leave nothing to chance.

The night before battle some 2,000 of his knights covered themselves up with grass, ready for a massive ambush of the Huastecan army. On the next day, when the Huastecans attacked, Moctezuma’s men bolted and pretended to run away in panic. When the Huastecans followed, shouting for victory, the waiting warriors sprang up and attacked them, defeating them completely.

The Aztecs fought largely to gain prisoners for human sacrifice, not to kill, as did the Spanish. After the victory of Moctezuma, many—if not all—of the Huastecan captives had their hearts cut out by obsidian knives to feed the thirsty gods of the Aztecs.

When Hernán Cortés landed on the gulf coast at what is now Veracruz, it seemed impossible that he would ever achieve his goal of conquering the Aztec Empire. Yet, many of the subjugated peoples, hating the Aztecs for their exorbitant taxation and human sacrifices, joined him in his war. In 1521 the Aztec Empire fell, its last emperor Moctezuma II either stoned to death by his people for appearing to collaborate with the Spanish or garroted by the orders of Cortés.