|

| Shona |

The Shona is the name used to describe a number of tribes with similar cultures who have lived in the eastern part of Zimbabwe. The main tribes are the Zezuru, the Karanga, the Manyika, the Tonga-Korekore, and the Ndau. All speak Bantu and have survived in farming communities.

They made up some 80 percent of the population of Zimbabwe in the year 2006, with the president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe (prime minister 1980–87, president from 1987), being from the Shona, as was the prime minister of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, Bishop Abel Muzorewa.

There are also many Shona in neighboring countries: Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zambia. Some also lived in the short-lived Republic of Venda, one of South Africa’s homelands or “Bantustans,” established 1979–94.

|

Traditionally the Shona were farmers of millet, sorghum, and maize, the last being their major staple food. They currently grow many other crops, including beans, groundnuts (peanuts), rice, and sweet potatoes.

For meat, the Shona hunt animals. Cattle are raised—not for beef but for milk, and also for a measure of wealth, especially for paying dowries. The main migration of the Shona to modern-day Zimbabwe was largely associated with finding grazing land for their cattle.

Living conditions largely consist of villages that involve clusters of huts around a central area where granaries and common cattle pens are located. Huts are made from mud and wattle, with thatched roofs, and generally accommodate extended families.

The kinship system involves exogamous clans, with family trees and traditions, succession, and inheritance generally following the male line, although a few groups of Shona in the north of the country are matrilineal. Chiefs who inherit their position in the male line run the villages.

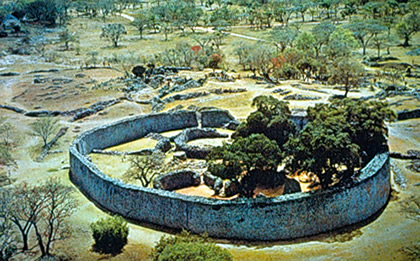

In the ninth century the Shona built the great stone buildings of Great Zimbabwe, one of the most important archaeological sites in southern Africa. The word Zimbabwe, which became the name of the country, means “royal court,” and they were the centers of power in the land.

There are three sections that make up Great Zimbabwe: the Hill Complex, the Great Enclosure, and the Valley Complex. The Hill Complex has been called the Acropolis by some historians and was the center of royal events in the whole site. Although it has a number of enclosures, they were probably for animals rather than for protection.

Archaeologists have been able to show that it was built in a number of stages, and modified at different times. Some of the buildings collapsed, and the site was then leveled before new building work was started. The eastern section is known as the “ritual enclosure” and is connected with ceremonies involving Shona chiefs.

Large statues of carved soapstone birds looked over the site but were removed long ago. There is also some evidence of gold smelting in one section nearby. There are various theories for the small towers, with some scholars suggesting religious purposes, and others that they provided lookout positions.

The most famous part of Great Zimbabwe is the Great Enclosure, which is one of the most regularly photographed parts of the entire area, appearing regularly in books and on Rhodesian and Zimbabwe postage stamps. Nearly 255 meters in circumference and 100 meters across, it remains the largest surviving ancient structure in sub-Saharan Africa.

Scholars have long surmised it was a royal compound where the king’s mother and his main wives would reside. There was a belief that the large conical tower on the site held treasure, and it was marked on some plans as being the site of the royal treasury.

Many people have dug in the hope of finding gold, but it is also believed that it was the grain store for the king. The Valley Enclosures date from the 13th century and have yielded the largest amount of archaeological finds.

There was much speculation on whether the Shona actually built the enclosures at Great Zimbabwe, with some writers surmising that they were Arab, Egyptian, Ethiopian, Greek, Jewish, or Phoenician in origins. Some have sought to link them to the queen of Sheba or the legendary Prester John. Others have seen connections with the famed King Solomon’s mines.

However not a single archaeological link connects the ruins with any of these. Some Chinese porcelain, Persian crockery, and beads and a few trinkets from India were found, indicating that the people at Great Zimbabwe traded, probably through intermediaries such as the Arabs, with peoples in the Indian Ocean.

The first Caucasian to see Great Zimbabwe was Adam Renders, an American sailor, who arrived in the area in 1867. He married the daughter of an African chief and remained nearby until his death in 1881.

The first to write an account of the ruins was Carl Mauch, a German who came to Great Zimbabwe in September 1871. Subsequent travelers started taking pieces of the ruin away with them.

British archaeologist Gertrude Caton-Thompson spent three years working at the site in the 1930s and concluded that they were Bantu in style, and part of the legendary Shona civilization.

Great Zimbabwe remains the second most important tourist site in Zimbabwe, after Victoria Falls. In recent years Shona culture and customs has been revived with an interest in Shona wood and stone carving, and music.