Olaf Tryggvason ruled the kingdom of Norway as Olaf I. He was the son of King Tryggve Olafsson but was forced to flee when Eric Bloodaxe killed his father and purged the royal family.

Olaf finally found refuge in Novgorod, where the Vikings had opened up settlements. Their renown as warriors made them prized mercenary soldiers throughout eastern Europe; as many Vikings went east as those who made the more familiar inroads into western Europe.

Their fighting prowess was so well regarded that the emperors of the eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire made them among their prize troops as the Varangian Bodyguard. The huge axes they carried as their main weapons earned them fear and respect from their enemies.

|

Olaf served in Novgorod under Vladimir I (Vladimir the Great) (c. 958–1015), who converted the Rus, the ancestors of today’s Russians, to Christianity in his principality of Kievan Rus. Olaf also saw service as a mercenary under the Holy Roman Emperor Otto III (960–1002).

After his sojourn in eastern Europe where he married a Polish princess, he became involved in the Viking raids on England and France. After the death of his Polish wife, he wed Gyda, who was the sister of Olaf Kvaran, the Viking king of Dublin. Ireland, as England, suffered greatly from Viking incursions from Scandinavia.

But as in France and England the Vikings created permanent settlements and Dublin traces its origin to the Viking settlement. Dublin on the river Liffey would have proved an excellent and protected anchorage for the Viking long ships.

It would not be until 1014 that the Irish High King Brian Boru would defeat the Vikings at Clontarf, effectively restoring much of Ireland to native Irish rule. However, Brian was killed toward the end of the battle.

Olaf learned of the dissatisfaction of the Norwegians with the rule of the earl Haakon. He decided to make a dramatic bid for his father’s throne. The people welcomed him as the rightful king and he swiftly became established as ruler of the kingdom.

|

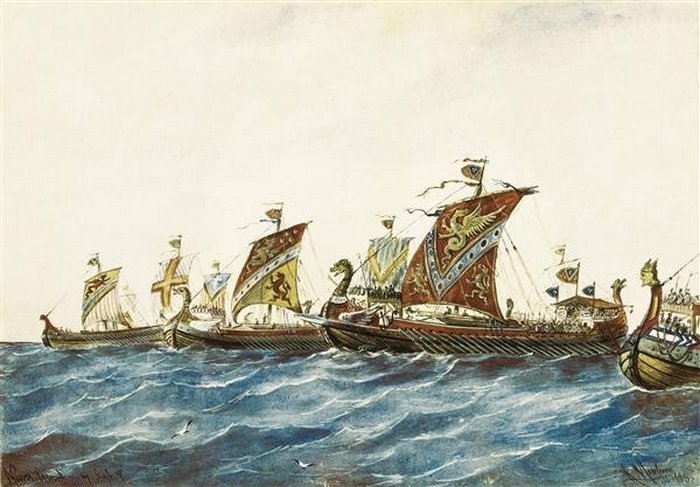

| Olaf long ship |

Johannes Brondsted writes in The Vikings that Haakon “was murdered by one of his own servants.” However, in c. 995 Olaf converted to Christianity and, as was the custom of the times, caused his people to convert with him.

During the conversion of Norway, he had the shamans who opposed him drowned at high tide. Once he had made his conversion, Olaf ceased raiding Christian countries and turned his considerable energies to raiding pagan countries.

The date of Olaf’s conversion to Christianity is disputed. Johannes Brondsted in The Vikings remarks how Olaf raided England in 991. In 994 he participated in a massive raid on London with the Danish king Sweyn (Swen) Forkbeard. Brondsted notes that Olaf had already been converted to Christianity.

|

The raid was a large undertaking, according to Brondsted, “with a joint fleet of about a hundred longships, and presumably at least two thousand men, they attacked London; but the city beat off the assault, and the Vikings had to be content with plundering southeast England and finally accepting 16,000 pounds of silver to leave.

Olaf Tryggvason left for good to take up the task of conquering Norway.” At the time, Ethelred was the king of England. Olaf made his capital at Nidaros, now known as Trondheim, when he took the Norwegian throne.

Upon taking the throne in 995 Olaf enforced Christianity among the general population, but his rule was only certain in the north around Trondelag. His former ally Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark claimed the southern part of Norway.

While Olaf tried to consolidate his rule in Norway, he also controlled Iceland. He made a strong effort to convert the inhabitants of Iceland from their pagan ways.

While the first missionaries, Brondsted notes, were sent in 987, their journey ended in failure. Around 997, however, Olaf’s efforts met with success and Christianity was proclaimed at the Icelandic Thing, perhaps the closest to a true democratic assembly then in existence in northern Europe.

Meanwhile Olaf’s attempt at consolidation was bringing him nearer to a confrontation with Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark. Sweyn, seeing a conflict ahead, carefully wove a web of alliances around Olaf.

Sweyn married the mother of the king of Sweden, Olaf Skotkönung. He was careful to include the sons of Earl Haakon in his marital alliances as well. One son, Swen, was married to Skotkonung’s sister, while the other, as Brondsted notes, was wed to Sweyn Forkbeard’s own daughter.

In 1000 Olaf met his enemies at a naval battle off the island of Svold, near Rugen. Olaf was greatly outnumbered by the fleets of Denmark and Sweden, in addition to those Norwegians who followed the two sons of Earl Haakon. Moreover, as Brondsted writes, the Viking fighters known as the Joms-vikings also betrayed him.

Olaf fought bravely from the deck of his ship Long Dragon, which was reputedly the largest warship yet seen in Scandinavian waters. The rowers of Viking longships, it should be noted, were warriors as well and not slaves as they were on the galleys of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

When the ships came in close contact, sometimes efforts were made to ram an enemy’s ship. But, as with the Romans, battle was decided by an armed conflict among the warriors, who would attack an enemy vessel and seek to overpower the crew.

Destroying a longship was never a real tactical goal, since the attackers usually sought to take it intact and add to their fleet. This certainly would have been the case with Olaf’s Long Dragon. After his death, Olaf remained the hero of his people, who whispered that he was still alive and waited for his return in vain.