The man who became the third ruler of China’s Ming dynasty (1368–1644) as Emperor Yongle (Yung-lo) (meaning “lasting joy”) was the fourth son of Zhu Yuanzhang (Chu Yuan-chang), the dynastic founder. His personal name was Zhu Di (Chu Ti).

Well grounded in Confucian studies and also a proven military commander, he personally led expeditions deep into Mongolia. Granted the title prince of Yan (Yen) by his father, he was also appointed commander of a large garrison that guarded Yan and the former Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) capital Dadu (T’a-tu).

Zhu Yuanzhang, who is known as Emperor Hongwu (Hung-wu) and posthumously as Taizu (T’ai-Tsu), appointed his eldest son the crown prince, and the crown prince’s eldest son as his heir when the crown prince died before him.

|

Taizu died in 1398 and his 20-year-old grandson succeeded as Emperor Jianwen (Chien-wen). The young emperor and his advisers at once made political changes that included purging his uncles (sons of Taizu), some of whom commanded troops guarding against Mongol invasions.

These provoked a crisis and war when Jianwen seized two of the prince of Yan’s officials and carried them off to Nanjing (Nanking), the then Ming capital, for execution. As the eldest surviving son of Taizu the prince of Yan accused his nephew of persecuting the princes and wrongfully changing the direction set by the dynastic founder.

Hostilities began in 1399 with an attack by the emperor’s forces. The prince, who was a superb commander and strategist, had about 100,000 troops. The emperor had over 300,000 men but they were less well led. After a hard campaign the gates of Nanjing were opened to the prince’s army on July 13, 1402.

In the melee the palace caught fire and when the fire died out three badly burned bodies were found and declared to be those of Jianwen, his empress, and their eldest son (his second son was two years old and lived for many years in protective custody).

|

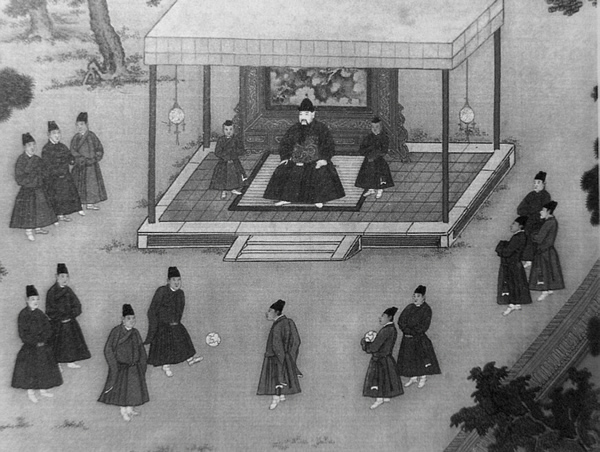

| The Yongle Emperor observing court eunuchs playing cuju |

Because there was no proof of the authenticity of the corpses, searches for Jianwen continued for many years and legends proliferated about what had happened to him. (Many years later he was found and identified by a birthmark, living as a Buddhist monk, and was allowed to live out his life.) Zhu Di thus became emperor, not the successor of his nephew, but of his father. He chose the reign name Emperor Yongle. Jianwen’s supporters were purged.

Emperor Yongle is regarded as the second founder of the Ming dynasty because of his numerous accomplishments and the expansion of the empire under his rule. A professional soldier, he took great interest in military affairs.

To prevent a recurrence of his own rebellion against the reigning emperor, he removed his brothers and younger sons from active command, reorganized the army, and rotated provincial units to frontier duty and campaigns.

|

Since the northern frontier remained vulnerable, and since his new capital Beijing (Peking) was close to the borderland, he emphasized defenses in the north, taking measures to ensure good communications, grain transport, and logistical support for the troops and settling many on the frontiers as soldier-farmers.

He used both diplomacy and military action in relationships with the nomads to ensure Chinese interests and to prevent them from becoming allies of the Mongols in the northwest. Likewise he conciliated the various Jurchen tribes in Manchuria to gain their submission as vassals. Over a century earlier the first Yuan ruler, Kubilai Khan, had obtained control over Tibet.

As Mongol power collapsed, Tibet went its own way under a fractured political-religious system. Yongle did not attempt to gain political control over Tibet and treated its top clergy with respect and lavished gifts on them when they visited, happy that they were not united, and therefore could not threaten his borders. His main concern was over the Mongols.

Between 1410 and 1424 he personally led five campaigns into Mongolia, each with over 250,000 troops, falling ill and dying during the last one. His goal was to forestall the formation of Mongol alliances and while he scored victories each time, he could not destroy them or prevent them from coalescing again. Following his death Ming strategy changed to a defensive one.

To secure China’s primacy in the Asian world Taizu had obtained Korea’s vassalage (following the fall of the Yuan dynasty Koreans too threw out the Mongols. A new dynasty, called Yi or Choson, was established in 1392). In 1407 Yongle sent an army to conquer Annam (modern North Vietnam), a vassal state, because of involvement in local politics.

The Chinese army crushed the Annamese army in battle and annexed the region as Chinese provinces. The Annamese, however, waged a guerrilla war of resistance that was costly to China. Finally, in 1427, three years after Yongle’s death, a peace agreement was reached whereby Annam ruled itself but acknowledged Chinese overlordship.

Between 1405 and 1422 Yongle sent six huge naval expeditions under a eunuch admiral named Zheng He (Cheng Ho) that showed the Chinese flag from Southeast Asia, across the Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, to East Africa and brought about trade and acknowledgment of Chinese overlordship from numerous small states throughout the region.

|

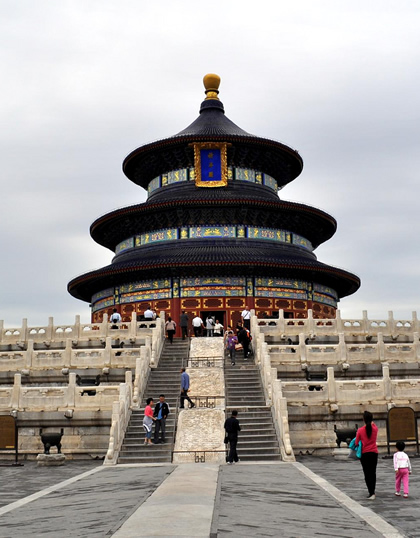

| Temple of Heaven |

Nanjing was an unpleasant memory to Yongle, who rebuilt the Yuan capital Dadu (T’a-tu); named it Beijing (Peking), meaning Northern Capital; and moved his government there in 1421. He built its imposing city wall, the imperial palace (residence and office) of over 9,000 rooms, the Temple of Heaven, many temples, and a huge mausoleum for himself outside the city.

In government he continued and expanded institutions and practices begun by his father, which became the fixed pattern of administration through the dynasty. The examination system continued to produce talented men for the government, the best among whom were recruited to the Hanlin Academy, which helped the monarch to draft laws, process documents, and deal with problems.

Highly educated and author of philosophical essays, he gathered more than 2,000 scholars who worked for five years to produce a work called the Yongle Dadian (Yung-lo t’a-tien) comprising 11,469 large volumes and over 50 million words. It was an encyclopedia of knowledge in all fields.

His sponsorship of intellectual life resulted in many other literary projects and publications, printed in large numbers and widely distributed, this half a century before Johann Gutenberg’s first printed book. Yongle’s accomplishments earned for him the posthumous title on Chengzu (Ch’eng-tsu), which means “successful progenitor.”