|

| Sui Dynasty |

This short-lived dynasty (581–618) is enormously important in Chinese history because it restored unity to a country that had been divided since the fall of the Han dynasty in 220.

For 300 years before its creation China had moreover been divided between the Turkic tribal people called the Toba (T’o-pa) and Xianbi (Hsien-pi) who ruled the north and Chinese, many descended from refugees who had fled the nomadic invaders, who ruled the south.

As the short-lived Qin (Chin) dynasty (220–206 b.c.e.) that it has been compared to, the Sui heralded China’s second great imperial age under its successor, the Tang (T’ang) dynasty. The last of a succession of mostly short-lived states of northern China ruled by Turkic tribal people was called the Northern Zhou (Chou).

|

The second Northern Zhou ruler was married to the daughter of a powerful nobleman named Yang Jian (Yang Chien), the duke of Sui. When he died leaving a six-year-old son as successor, grandfather Yang became regent and soon seized power and founded a new dynasty named the Sui, in 581.

Sui Wendi

Yang Jian (r. 581–603) is known by his reign title Sui Wendi (Wen-ti), meaning “literary emperor of the Sui.” Of mixed Chinese and Turkic descent, he was a prudent, hardworking, and wise ruler and was assisted by his capable Turkic wife, Empress Wenxian (Wen-hsian).

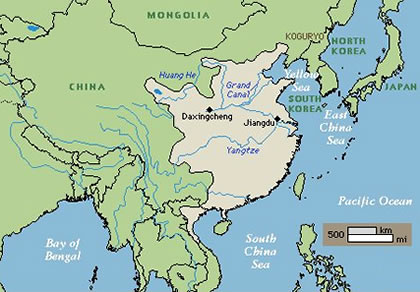

He established his capital in Chang’an (Ch’ang-an), which had been capital city of the Han dynasty, symbolizing his goal of restoring its institutions and glories.

|

| Sui Wendi |

Between 587 and 589 he subdued southern China, reunifying the country. Though a devout Buddhist, he used Buddhism, Daoism (Taoism), and Confucianism to win support and to establish a common cultural base for the country.

Wendi curtailed the power of the great landed families by vesting in the central government the power to appoint all officials throughout the land and laid the foundations for personnel recruitment through a nationwide examination for which the successor Tang (T’ang) dynasty is usually given credit.

Wendi also began a nationwide land allocation system for farmers and a militia system in which all male farmers who had been given land were obliged to serve. These policies were also fully realized under the succeeding Tang dynasty.

|

Wendi waged inconclusive campaigns against the northern Turkic tribes and the newly formed state that occupied northern Korea and southern Manchuria called Koguryo. He also rebuilt sections of the Great Wall.

Wendi was frugal in private life and worked to improve the economy by rebuilding old canals to link Chang’an with the Yellow River and expanding the waterways to link up with the waterways of central China and the Yangzi (Yangtze) River.

His son and successor later expanded on the waterways, known as the Grand Canal, in the north to Luoyang (Loyang) with a branch to present day Beijing, and in the south to Hangzhou (Hangchou) on the coast, via Yangzhou (Yangchou) on the Yangzi River. Its total length was 1,250 miles, the longest canal system in the world and a huge engineering feat.

This grand project was completed by corvee labor and at great human cost, which generated popular discontent against the dynasty. Its completion was of immense importance because the system linked the rich and growing economy of the south to the heart of the empire in the north to support the needs of defending the empire. The Grand Canal also aided in the reintegration of the long divided empire.

Wendi and his empress had five sons. The second son, Yang Guang (Kuang), known to history as Yangdi (Yang-Ti), was born in 569. Talented and well educated, Yang Guang was married to a woman from the royal family of the former Liang dynasty of southern China and appointed viceroy of the newly pacified southern provinces in 589, where he remained for 10 years.

He ruled from Yangzhou, which flourished as the junction that connected the Yangzi River with prosperous Hangzhou on the coast. In a series of murky events that might have implicated Yang Guang, his elder brother the crown prince was demoted, he was elevated to that position, followed shortly by Wendi’s death.

Yangdi (Yang-Ti)

|

| Sui Yangdi |

Yang Guang reigned as Yangdi (Emperor Yang) from 604 to 617. Historians have accused him of megalomania and extravagance that brought down the Sui dynasty. His grand vision led to the simultaneous launching of huge projects that include the building of a second capital in the east, at the site of the former Han capital of Luoyang that had been sacked by the Xiongnu (Hsiungnu) 300 years before.

He further expanded the Grand Canal begun by his father, building an eastern branch to modern Beijing. Yangdi also lived extravagantly and traveled extensively along the canals and rivers in a grand flotilla of pleasure boats and held elaborate entertainments in his lavish palaces. His downfall was however triggered by his ambitious foreign policy and disastrous wars.

In the south Wendi had restored Chinese power in present-day northern Vietnam, which had been annexed under the Han dynasty but had broken away from the control of the weak southern dynasties in the era of division.

|

| dragon boat of sui dynasty |

Yangdi invaded the Champa kingdom in presentday central and southern Vietnam, which won acknowledgment of Sui overlordship by the local ruler after a costly campaign.

A naval expedition was sent in 610 to pacify islands in the East China Sea, generally assumed to be Taiwan, but formed no permanent settlements there. Chinese ships had sailed to Japan since the Han dynasty, where Chinese cultural influence, brought via Korea, had been growing.

The first Japanese embassy arrived in Yangdi’s court in 607 and addressed him as “the Bodhisattva Son of Heaven who gives the full weight of his support of Buddhist teachings.” It included Japanese Buddhist monks, who sought permission to study Buddhism in China.

Yangdi sent an emissary to Japan in 608 that brought back more information about that country. Thus opened a two-century-long era when 17 Japanese embassies, each with hundreds of students, arrived to study in China, with great significance for Japan’s development.

In the north Yangdi, too, had to deal with the Turks. To keep them in check he rebuilt and extended sections of the Great Wall. He also resorted to traditional stratagems such as keeping sons of the Turkish khans in the Sui capitals to ensure their fathers’ good behavior, conferring Sui princesses in marriages with the khans, trade and gifts (Chinese silks for Turkish horses), and Chinese titles for Turkish rulers.

His diplomats also fomented dissension among the Turkish tribes to prevent them from coalescing or forming coalitions against China. When necessary Chinese armies overawed and defeated hostile tribes. The Sui maintained dominance over the Turkic tribes and kept open trade routes between China and the west.

In the northeast in lands where the Han had established several commanderies, a state called Koguryo had formed early in the seventh century, with its capital at modern Pyongyang and that incorporated lands of modern northern Korea and Manchuria east of the Liao River.

|

| sui soldiers |

The Korean campaigns and natural disasters added to the economic distress and widespread revolts broke out. Ultimately the Sui were defeated by the difficult terrain and the climate, which favored the defenders; the great distance of the campaign from the heartland of China (about a thousand miles); and the weak coordination between the Sui army and navy.

With the empire collapsing Yangdi left his capital for the south via the Grand Canal. Two years later he was murdered in his bath and the Sui dynasty ended.

Influence of the Sui Dynasty

Historians have judged Yangdi harshly for his personal debauchery and as a tyrant who brought down the dynasty his father founded.

However the debacle his policies brought and the civil war that ensued did not last long and China would enter its second imperial age under the successor Tang dynasty. The glories of the Tang dynasty have overshadowed the contributions of the Sui. They include:

- The sweeping away of the regional regimes and their institutions that had divided China in the preceding three centuries. It built new institutions that would ensure future political and cultural unity in a subcontinental sized nation that stretched from Beijing to Hanoi and from the East China Sea to the gates of Central Asia. At the height of Yangdi’s reign the Chinese empire governed about 50 million people.

- The modeling of a reunified China on the Han by reviving and expanding institutions such as the examination system based on the Confucian classics and the Han tradition of codified laws (the Sui code became the bases of the Tang and later codes).

- A land tenure and militia system that would be maintained by the Tang for a century and half, which was key to its success and was copied by Japan and has inspired later Chinese governments because they were just and equitable.

The Sui succeeded in reunifying China because of the wise policies of its founder but also because despite partition, the Chinese shared a common written language, common ideology and moral values in Confucianism, and by now a religion that was deeply embedded throughout the land: Buddhism.