The last independent ruler of the vast Inca Empire, Atahualpa Inca was seized by the forces of Francisco Pizarro in Cajamarca, Peru, on November 16, 1532. He was held prisoner pending payment of an enormous ransom, and after the ransom was paid, he was executed for treachery on July 26, 1533.

Atahualpa’s name and legacy have come to be associated with Spanish avarice and duplicity in their conquests in the New World. His legacy will also be forever tied with indigenous political factionalism and incomprehension of the larger threat posed by European invasions, and with the persistence of pre-Columbian Andean culture and religiosity long after the Spanish military conquest of Peru was complete.

Upon the death of their father, Huayna Capac Inca, in 1525, the brothers Atahualpa Inca and Huascar Inca were granted two separate realms of the Inca Empire: Atahualpa the northern portion centered on Quito, and Huascar the southern portion centered on Cuzco. In keeping with a longstanding Inca and Andean tradition of fraternal conflict, Atahualpa rebelled against his brother and imprisoned him.

|

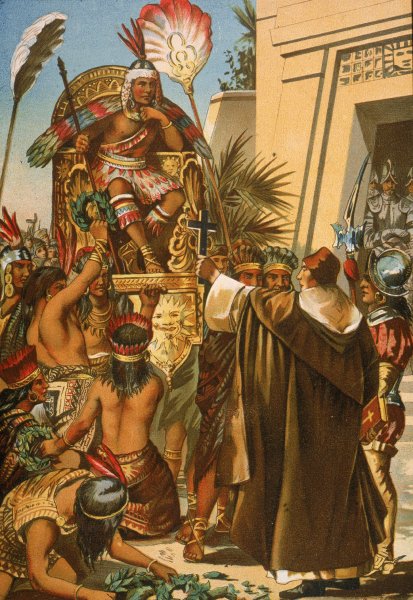

Pizarro and his men had the fortune of ascending into the Andes just as Atahualpa was returning to Cuzco after successful conclusion of his northern campaigns. After launching a surprise attack in Cajamarca and massacring upward of 6,000 Incan soldiers, Pizarro took Atahualpa prisoner.

To secure his release, Atahualpa pledged to fill a room of approximately 88 cubic meters with precious golden objects, the famous Atahualpa’s ransom. Over the next months, trains of porters carted precious objects from across the empire, including jars, pots, vessels, and huge golden plates pried off the walls of the Sun Temple of Coricancha in Cuzco.

|

| For more than 100 years, the Incan army was virtually undefeated. That all changed when the Spanish arrived. |

On May 3, 1533, Pizarro ordered the vast accumulation of golden objects melted down, a process that took many weeks. Finally, on July 16, the melted loot was distributed among his men, and 10 days later, Atahualpa was executed.

The eight months during which Pizarro held Atahualpa prisoner provided the Spanish with ample opportunity to observe the Inca leader’s customs and habits and the relations between him and his people.

Their detailed descriptions offer valuable insights into the profound reverence with which the Inca was regarded, his semi-divine status, and the social hierarchies and relations of the Inca realm. While being held prisoner, Atahualpa secretly ordered the assassination of his brother Huascar, an act that provided the Spanish with a ready pretext for executing him.

|

Atahualpa’s execution provoked a fierce debate in Spain regarding the morality of the act, and of the conquest more generally. King Charles wrote to Pizarro of his displeasure, while other prominent Spaniards also condemned the execution. One result was that the Crown decided to treat Atahualpa’s descendants with considerable respect and deference.

His sons and other family members were granted privileged status, and Atahualpa’s many descendants ranked among the most socially privileged of Indians in post-conquest colonial society. In subsequent decades, he was also transformed into a martyr in the cause of Indian resistance to Spanish domination.

|

| Capture of Atahualpa |