The largest and second most important political jurisdiction in Spain’s American empire after the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the Viceroyalty of Peru came into being in 1542 during the civil wars that wracked the Andes during the conquest of Peru.

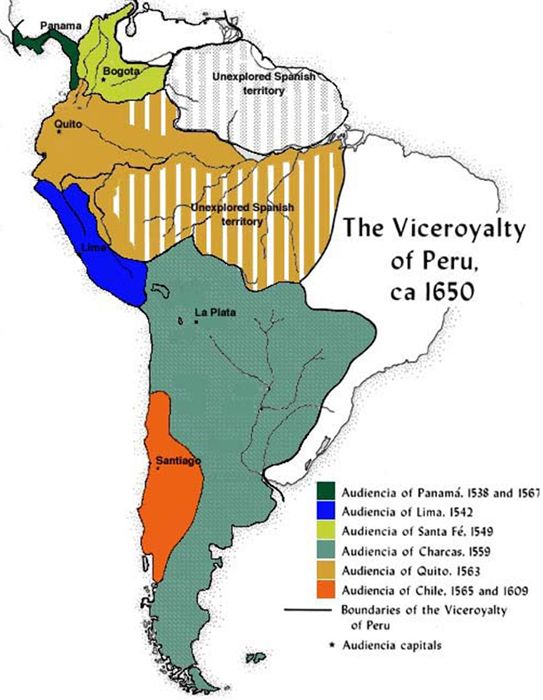

Originally comprising all of South America west of the demarcation line established in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, the viceroyalty extended from Panama in the north to Patagonia in the south, and from the Pacific Ocean eastward to a longitudinal meridian at roughly 44 degrees west, excluding parts of northern South America (contemporary Venezuela), which were under the jurisdiction of New Spain. In the late colonial period the Crown carved two new viceroyalties out of the Viceroyalty of Peru: New Granada (1739) and Río de la Plata (1777).

Following the civil wars of the period of conquest, and the major reforms of Viceroy Francisco de Toledo in the 1570s, Peru emerged as a major source of silver bullion, especially from the “mountain of silver” at Potosí.

|

As elsewhere in the Americas, Spain imposed across the Peruvian Andes a rigid castelike race-class hierarchy in which subordinate Indians, toiling under a modified version of the preconquest mita labor system, provided labor and tribute to Spanish civil and ecclesiastical authorities, and to native kurakas, or community chieftains, who occupied an ambiguous middle ground between the Spanish elite and the masses of Indian laborers.

The violence of conquest and its aftermath prompted a millenarian nativist backlash in the 1560s: the Taki Onqoy movement. Aiming to expel the despised invaders and reestablish a pan-Andean indigenous state, this popular rebellion reproduced many of the divisions and fractures of preconquest indigenous society and was crushed by the 1570s. Popular memories of Taki Onqoy endured throughout the colonial period, however, reerupting in a different form in the major Andean rebellions of the 1780s.

As elsewhere in the Americas, demographic declines in colonial Peru were very steep, though on the whole of a lesser magnitude than those in New Spain (though, as elsewhere, the numbers will never be known with any degree of precision). From an estimated population of 9 million in 1520 for the Andes as a whole, the number of surviving Indians is estimated to have dropped to 1.3 million by 1570, and 600,000 by 1630.

Following a major series of epidemics in 1718–20, the population hovered at around this number to the mid-1700s, climbing gradually thereafter. In a characteristic pattern, highland dwellers on the whole experienced a lesser population decline than inhabitants of the more disease-prone lowland valleys of the Pacific Coast.

Despite the ravages of warfare, forced labor, forced conversion, disease, and the violence of colonial rule, Peru’s indigenous peoples and communities displayed a remarkable resilience, retaining many features of their preconquest cultures and lifestyles.

Despite prodigious efforts, Spanish authorities were never able to extirpate the religious beliefs and practices of Peru’s Indian peoples, while Quechua, Aymara, and related tongues remained the dominant languages among the vast majority.

Centuries-old traditions of planting, harvesting, cooking, eating, herding, weaving, and, in general, conceiving of and acting in the world endured through nearly three centuries of Spanish colonial rule and after, as remains plainly apparent to the present day. The English-language historiography on colonial Peru, like that for colonial Mexico, is exceptionally rich.