|

| Medieval Europe Educational System |

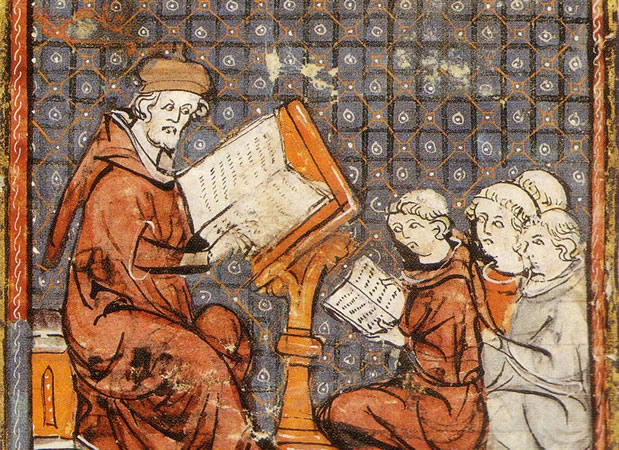

One of the most important intellectual developments in western Europe during the High Middle Ages was the growth of urban schools and universities in which fee paying students were able to acquire a basic education in the liberal arts. The system of education known as Scholasticism resulted from the rigorous application of the liberal arts and their principles to the study of God and the traditional teachings of the church.

These educational transitions were characteristic of the period that Charles Homer Haskins and subsequent scholars have dubbed “the renaissance of the 12th century,” a time of intense cultural flourishing spanning from around 1050 to 1215 and made possible by the rapid growth of cities and the emergence of a cash economy.

Since the time of Charlemagne two types of schools had existed in western Europe: monastic and cathedral. Monastic schools trained oblates (that is, children given to the monastery and the monastic life by their parents) in the scriptural, theological, and spiritual traditions of the church.

|

Monastic education emphasized acceptance and assimilation of what was known about God rather than investigation of the unknown. Cathedral schools, which were under the control of the local bishop, trained young men for careers in ecclesiastical or secular administration by providing a basic education in reading, writing, rhetoric, and documentation. Here again the curriculum was oriented toward the practical rather than the speculative.

In the first half of the 12th century a new type of school began to appear in burgeoning cities like Paris. These urban schools, which were open to all fee-paying students, served a clientele that did not necessarily have aspirations to serve the church or government in the traditional ways. The interpretation of sacred Scripture and the study of God remained, however, at the center of the curriculum of these new schools.

Teachers at the urban schools certified to give authoritative interpretations of revelation were officially designated masters. Masters such as Anselm of Laon, Bernard of Chartres, and Hugh of St. Victor sought to use the liberal arts as tools in the interpretation of revelation and to teach their pupils to do the same.

Thus the urban-school student would first read in the seven liberal arts before moving on to a higher discipline such as theology or law. In the 13th century the medieval university would come to be defined by a school of theology, a school of law, and a school of medicine beyond the liberal arts curriculum.

The seven liberal arts were divided into the trivium, the three arts proper, and the quadrivium, the four sciences. The trivium consisted of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic or logic. The quadrivium consisted of arithmetic, astronomy, geometry, and music.

About a millennium and a half before the birth of the medieval university, Aristotle maintained not only that all the arts and sciences are subservient to “first philosophy” (that is, the science of the end or the good), but also that they constitute the parts of philosophy as preparation for that highest wisdom that determines the end of all things and orders them accordingly. Thus subsequent pagan thinkers such as Cicero and Seneca insisted on the necessity of a liberal arts education for the formation and perfection of humankind.

Ancient Christian thinkers such as Augustine of Hippo and Jerome, also having been trained in the liberal arts, similarly insisted on the use of the arts in the interpretation of Scripture. The tiered curriculum of the medieval urban schools and universities owes much to Augustine’s understanding of the liberal arts as certain ordered steps intended to lead the student from corporeal to incorporeal things.

|

Hugh of St. Victor (c. 1098–1141), an early Scholastic theologian and master at the urban school of St. Victor in Paris, was known as the “Second Augustine,” even during his lifetime, because he used Augustine’s basic idea to develop a holistic well-ordered philosophy according to which the student is led from the timebound words of humans to the eternal Word of God.

According to Hugh, it is the ordered study of the liberal arts that ultimately leads the reader to the eternal Word or wisdom, the second person of the Trinity, who reorders and perfects the human student after the fall into the disorder of sin. In the urban schools the liberal arts were constitutive of philosophy, which Hugh and other medieval masters understood primarily as the love of that wisdom in whose image human beings are created and in whose image they are restored.

Liberal arts study intends to restore within fallen students the divine image, in Hugh’s view. The four major branches of philosophy into which the Victorine Master divides the arts arose as antidotes to humankind’s sickness because of the fall of Adam. First the theoretical arts (theology, physics, and mathematics, the last of which includes the quadrivium) seek to heal ignorance and restore humans to the knowledge of truth.

Second the practical arts (ethics or individual morals, economics or domestic morals, and political science or public morals) seek to heal concupiscence and restore humans to the love of virtue. Third the mechanical arts (weaving, armament construction, commerce, agriculture, hunting, medicine, and theatrics) seek to alleviate bodily weakness (an antidote to mortality).

Finally the logical arts (the trivium), which arose last of all, seek to provide a form of polished discourse on which the other branches of knowledge rely. The logical arts are therefore to be studied first, after which the student is to learn, in order, the practical, the theoretical, and the mechanical arts.

The second major phase of Hugh’s pedagogical program is the study of sacred Scripture, for which the pupil is to use the recently acquired tools of grammar, dialectic, and the other arts. The 12th-century application of grammar and dialectic to the study of God was central to theology’s becoming a science or academic discipline.

The most important theological and ecclesiastical works of the 12th century resulted from the rigorous application of the principles of dialectic to the enormous and disparate body of statements of the fathers and councils of the church on innumerable questions of faith and doctrine: for example, Peter Abelard’s Yes and No, the Ordinary Gloss, Peter Lombard’s Four Books of Sentences, and Gratian’s Concordance of Discordant Canons (Decretum).

Whereas various “questions” about God and God talk first developed out of the biblical witness and closely followed its narrative structure (as in Hugh of St. Victor’s On the Sacraments of the Christian Faith), in the following centuries theological reflection would take the standard form of the “questions” themselves systematically arranged in summae (as in the Summa theologiae of Thomas Aquinas).