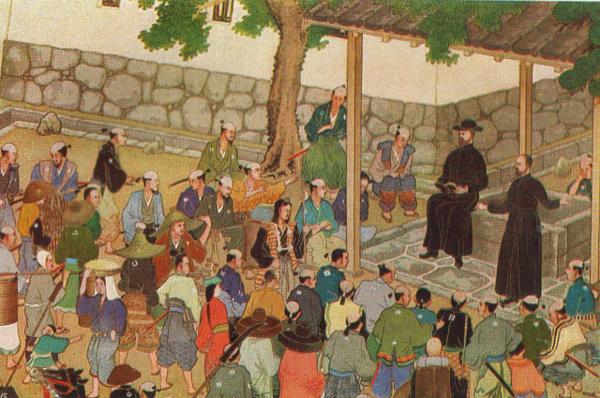

Francis Xavier, a founder of the Society of Jesus, arrived in Japan in 1549, inaugurating a century of Catholic Christian missionary activity in that country. After enjoying enormous success, Christians suffered brutal persecution and were almost eliminated a century later.

Japan was ruled by warring feudal lords in the mid-16th century who sought to wrest power from the failing Ashikaga Shogunate. These lords eagerly welcomed the newly arrived Portuguese to their domains in order to purchase European firearms.

Observing the respect the Portuguese merchants showed toward Catholic priests, many Japanese lords converted to the new faith and ordered their subjects to convert also. Some Japanese even mistakenly thought that Christianity was a variant form of Buddhism. Jesuit missionaries came under the protection of the Portuguese Crown and were soon joined by the Franciscans, who came via Spain’s colony the Philippines and were under the protection of Spain.

|

The southern island of Kyushu as well as the imperial capital Kyoto became centers of Christian missionary activity. Japan became the most successful area of Christian conversion in Asia. By 1582, an estimated 150,000 had become Christians, with the number rising to 300,000 by the century’s end, and 500,000 at its height in 1615.

Christian missionaries were welcomed as allies by Japan’s first aspiring unifier, Oda Nobunaga (1534–82), in his military confrontation with powerful Buddhist sects. Oda destroyed his formidable Buddhist opponents and their castles, but was assassinated. He was followed by Hideyoshi Toyotomi (1536–98), who continued the wars of unification.

Hideyoshi was ambivalent toward Westerners, on the one hand welcoming their trade. He also feared their influence, both the authority of the pope and Spain’s colonial ambitions, which had made the Philippines a colony. Thus he banned all missionary activities in 1587, but did not enforce the law until 1597, when he ordered nine missionaries and 17 Japanese Christians executed.

Hideyoshi died in 1598. Another succession struggle ensued until another nobleman, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542–1616), won a definitive battle in 1603, after which he was confirmed shogun by the emperor, thus inaugurating the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603–1868).

|

| Martyr of Japan |

The newly victorious and as yet insecure Tokugawa Ieyasu regarded Christians as potentially subversive and began to move against them in 1606. His son and successor continued his policies, expelling missionaries and ordering noblemen and ordinary people in his domain to renounce Christianity; he went so far as to execute those who remained Christian clandestinely.

The shogunate then forced all lords throughout Japan to conform to anti-Christian laws. Suspected Christians were forced to trample on the cross or other Christian symbols while those who refused were tortured to death.

Persecution climaxed in 1637–38 when oppressed Christian peasants revolted in western Kyushu. They were put down and slaughtered. A law in 1640 compelled all Japanese to register at a local Buddhist temple. Christianity was wiped out in Japan except for a few small underground communities.

|

The Catholic Church recognized 3,125 Japanese martyrs between 1597 and 1660, several of whom were beatified by Pope John Paul II. The Tokugawa Shogunate enacted other laws that banned trade with Europeans except for two Dutch ships annually and took other measures that almost totally isolated Japan from the Western world until 1854.

Thus between 1549 and 1640, Japan presented the paradoxical picture of success and then total prohibition of the Christian missionary movement.

http://epicworldhistory.blogspot.com/2012/04/tokugawa-ieyasu-japanese-ruler.html