Not long after the Spanish colonies in the Americas started to generate massive wealth, pirates started to attack the ships, taking the gold, silver, and other treasures from the Americas to Spain and later from Brazil to Portugal. In addition to attacking ships, some of the more daring buccaneers, such as Francis Drake, went as far as attacking ports.

While some of the early raiders were freelance pirates, the cost of maintaining a ship and the ability to find a friendly port meant that many were privateers. These were French, Dutch, and more particularly English sailors, who operated in the Caribbean and in the Atlantic on behalf of their government, who had issued them a “letter of marquee,” allowing them to attack enemy shipping in times of war.

Often the news of the end of a particular conflict took a long time to reach remote outposts and as a result attacks often still took place in peacetime. Some pirates also regularly exceeded their “letters of marquee” and attacked any ships they came across.

|

Although privateers could use the excuse of attacking enemy ships in time of war, many modern historians are more understanding of their actions given the appalling Spanish treatment of the indigenous population of the Americas, from which they gained much of their gold and silver.

The initial attacks on Spanish ships sailing across the Atlantic led the Spanish to establish a treasure fleet from the 1560s. This involved a large number of ships, including many men-of-war, sailing together taking manufactured goods to the Americas and returning with gold or more often silver. By this time, the English, French, and Dutch had established settlements in the Caribbean, which their privateers used as bases in their attacks on the Spanish.

The English buccaneer Francis Drake managed to capture some of the Spanish treasure fleet in 1580 and sacked the ports of Santo Domingo and Cartagena in the Caribbean in 1585, and later that year attacked and sacked the port of Cádiz in Spain.

This led to the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604, which turned many of the English pirates into privateers, weakening the Spanish merchant navy and providing a large source of profit for English and Dutch traders.

While Francis Drake operated ostensibly for patriotic reasons, the Spanish denounced him as a pirate, and by the early 17th century, there were large numbers of pirates operating in the Caribbean. Many used isolated European settlements around the West Indies, with a few operating from their own bases in isolated bays.

A few places, such as Port Royal in Jamaica, became famous haunts of the pirates, growing rich but also becoming exceedingly dangerous places, gaining the reputation of being one of the “richest and wickedest” cities in the world. Other places used by pirates included the islands of Antigua and Barbados.

The Thirty Years’ War, which lasted from 1618 until 1648, led to renewed Protestant-Catholic conflict in Europe, which led to fighting in the West Indies, and British as well as Dutch ships attacked those belonging to Spain and France. It was during this period that English privateers and pirates started to use the Mosquito Coast of Nicaragua to establish bases, which allowed them to attack Spanish ports and Spanish ships with ease.

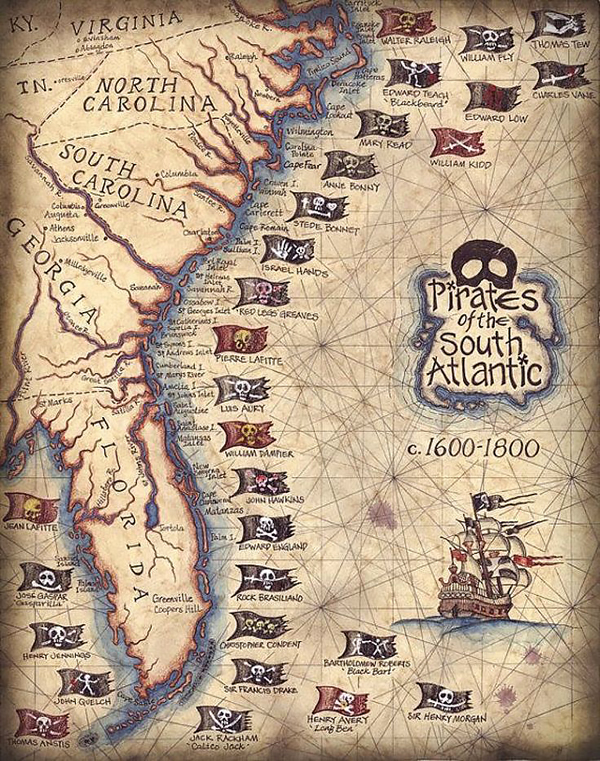

From 1660 until 1720, the so-called golden age of piracy, pirates again operated as privateers. This period saw some sailing under the famous “Jolly Roger” flag, with attacks by English pirates on both Spanish and French ships. There were also English attacks on the Dutch; the island of Saint Eustatius, a Dutch sugar island, was attacked by pirates and British soldiers on many occasions, changing hands 10 times during the 1660s and early 1670s.

|

French pirates also started operating freely from their ports on the island of Hispaniola (modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Sir Henry Morgan, a Welsh buccaneer, sacked the Spanish town of Portobelo in Panama, which had been well garrisoned.

Morgan later destroyed Panama City in 1671 but was arrested by the British, as the attack violated a treaty between England and Spain. At his trial in London, Morgan was able to prove he had no prior knowledge of the treaty and was released, knighted, and appointed lieutenant governor of Jamaica.

Other pirates such as Edward Teach, “Blackbeard,” became infamous not only for his savagery but for his outlandish appearance. He was killed in combat in 1718. There were also female pirates such as Anne Bonny, originally from Ireland, and Mary Read from London, who were captured and tried in 1720 in Jamaica, with both escaping execution.

The career of these two female pirates, which started when the former joined the crew of “Calico Jack” Rackham, and the second a ship captured by him, was related in many published books of the period.

After 1720, stronger European garrisons throughout the Caribbean caused a massive decline in the number of pirates operating in the region. At the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, the 1714 Treaty of Utrecht allowed the British to sell African slaves in the Americas, and many of the former pirate crews found that they were able to operate legitimately as slave traders.

The nations involved in Caribbean trade decided to eliminate the pirate threat to their lucrative trade routes. In 1720, two famous pirates, Charles Vane and “Calico Jack” Rackham, were hanged at Port Royal, and two years later some 41 pirates were hanged there in a single month.

Without the ability to seek refuge in places such as Port Royal, although some pirates continued operating through to the 1750s, they had access to fewer and fewer ports. This coincided with the European powers’ massively strengthening their hold on their West Indian possessions, and it became far more likely that pirates would be caught.

As a result there was a decline in piracy, with the former pirates having to find work in the slave trade, legitimate shipping, or the lumber industry, cutting logwood and later mahogany in what became British Honduras (modern-day Belize).

The romantic image of the pirates was nurtured by many writers, such as Daniel Defoe, who wrote A General History of Pyrates (1724), which described the lives of many of the more famous individuals, and much later Robert Louis Stevenson in Treasure Island (1883); a small number of pirates published their own accounts. The subject of pirates and piracy remains popular in today’s novels, plays, and films.