|

| Puritanism in North America |

Puritanism in North America is an extension to American shores of the challenge to the religious orthodoxy of England. With settlement came theology. Puritanism itself can be a diverse term and not one associated with a particular church or denomination.

Most Puritans were radical Protestants who arose following the Reformation in the late 16th century and who rebelled against some or all aspects of the Elizabethan religious sentiments of this period.

Influenced by the Calvinist theology of Protestantism found in Europe, Puritans felt that the existing Anglican Church’s practices and structures were corrupted and in need of “purifying” in order to purge the church of kings, idolatry, and popery. Their call was for strict biblical interpretation, and the creation of a “priesthood of all believers.”

Puritan believers should follow a clear moral path, which stressed God’s direct and total command of mankind’s place on earth. This belief system saw the individual directed by the grace of God, and as such, the believer must be obedient, disciplined, humble, and always grateful for God’s blessings.

To support such a system ceremonies should be simple, church decorations kept to a minimum, superstition should be confronted, education and Bible reading for all encouraged, clothing for priests and church members simple and free from adornment, and high personal morality practiced as a matter of faith. In time there would grow opposition to work or pleasure being taken on the Sabbath, drama, gambling, some forms of music, and even poetry if deemed sinful or erotic.

Church Structure

It was the Puritans’ challenge to church authority that brought conflict with the state, a factor that would lead to government persecution and the need to migrate to the New World to establish religiously inspired colonies on the Puritan model.

The Church of England was an episcopal hierarchy whose head was the monarch. This was the church of vestments, pomp, ritual, ecclesiastical courts, and the liturgical order of the Book of Common Prayer. It was this structure that permitted the perceived church decadence that the Puritans objected to.

Arguments for the presbyterian organizational model emerged in the 1570s, followed by the Congregationalist approach, which gave power to each congregation to organize themselves and choose their own church leaders. This latter model would come to dominate the church organization in New England and other colonies north of Virginia.

The Puritan struggles against the church and state did not win victories in the early 17th century and had to await the turbulence of the English Civil War

It was the Separatists who had given up reforming the Church of England who first established a permanent American colony. Sailing on the Mayflower and led by William Bradford

By 1630 other non-Separatist Puritans established themselves in Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the hub for the spread of varieties of Puritanism throughout what became New England. Numbers grew rapidly, reaching approximately 20,000 in 1640 and more than 100,000 by 1700. Splits also occurred within the Puritan ranks leading to the establishment of other Protestant colonies such as Rhode Island in the 1640s, which followed a Baptist tradition.

Other Protestant offshoots such as the Society of Friends or Quakers

The Puritan impact with its Calvinistic commitment to predestination, an acceptance of conversion as essential to spirituality, and belief in an elect membership within each church carried political dimension, which influenced governance in the major Puritan colonies.

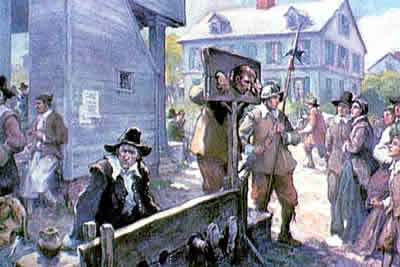

Some have argued that this mixture of church and state created a theocracy, particularly in Massachusetts Bay. Religious toleration, which was denied them in England, where they were viewed as dissenters, was not translated into general practice in their new lands.

As the decades progressed, difficulties arose as to how the power of the elect could be transferred to their descendents. The Half-Way Covenant was one device, but in time, particularly with political change in England following the Glorious Revolution in 1688, greater toleration of those deemed the nonelec developed both inside and outside the Puritan colonies by the 18th century.

Puritanism in North America helped make the successful settlement of prosperous English colonies a reality. Puritan belief in covenants, individual voices, simplicity, education, and morality would have a lasting effect on the development of democratic views and traditions, which, in turn, would have a major and lasting influence upon American life.